Back in the USSR, markets offered a variety of fresh produce, meat, cured fish, and other foods, whether from the nearby countryside or the other end of the country, that you’d have been hard-pressed to find in shortage-plagued stores. Just imagine: in the 1980s, in the dead of Moscow’s winter, you could buy a duck, a pineapple, and a tin of caviar, all under one roof, without standing on line for hours (all for a mere month’s worth of your salary). Today, things have changed. Moscow’s supermarkets carry pretty much any product you fancy, probably at a more affordable price. They remain open until late, when they don’t operate 24/7. Chances are there’s one a few minutes from where you live, whether that’s the city center or a remote suburb, whereas you’d have to take a subway and / or a bus to get to the closest market.

The situation is of course not unique to Russia. In Western Europe, markets have been challenged by the rise of the supermarket for decades. Yet they survive. They’re held only on certain days of the week (whereas the typical Russian market is open every day), and they gather a large number of sellers who offer a variety of products, raw or prepared, with an emphasis on freshness and quality, that a single grocery store would struggle to match. Particularly at a time when dedicated butchers, fishmongers, and produce stores have lost so much ground to the benefit of large grocery chains, markets are one of the bastions of quality food for those willing to pay the price. Some of the products sold at these markets aren’t local at all, and these aren’t farmers’ markets. These are sellers touring the various markets of a given area to hawk their products, the displaced artisans and shopkeepers of towns that have switched their high street preference from bakeries to banks, and from confectioners to cell phone stores.

Markets in the USA share some of the same characteristics, with some differences too. They also satisfy a desire for better quality and freshness, and increased food variety. They are, however, farmers’ markets. In large part, the vendors are farmers or farm workers who drive to various markets to offer their own products directly (although there are some artisans in the mix as well, selling prepared goods such as bread or pasta). Farmers’ markets neatly occupied the gastronomical vacuum left by the rise of the American supermarket in the 1970s and ’80s, their number growing from about 1,750 in 1994 to almost 4,400 in 2006, and up to more than 8,100 in 2013. While many people are happy to bring home fresh ingredients, some have grown so disconnected from cooking and from the concept of a market that they treat the places like museums where they take pictures, look at the food in polite amazement (“is a pastured egg the same as pasteurized?”), sometimes try a little sample of chutney-this or Brooklyn-that, but would never consider buying anything to eat at home – unless there’s a cupcake vendor, that is. The absurd and now closed New Amsterdam Market in NYC, a so-called “purveyors market” rather than a farmers’ market, seemed to cater precisely to that crowd.

So what’s a Russian market to do? Close? Sell quality products at a high premium? Provide an outlet for local farmers? Turn into an ethnological museum cum botanical garden? Let’s take a look at what the Danilovsky Market did…

The Danilovsky market is the oldest trading place in Moscow. It takes its name from the nearby Danilov Monastery, founded in 1282 by Alexander Nevsky‘s son, Daniel. Trade naturally flourished near the busy monastery, and it is assumed that the market has existed since the 13th or 14th century.

The market continued into Soviet times, and in 1963 it became a kolkhoz market. Following the 1965 Soviet economic reform, the market’s 1969 charter stipulated that it act on the basis of khozraschyot, or full cost accounting. At the time, it consisted of open stalls covered with canopies, and looked something like this:

Danilovsky Market circa 1975 – Photo by Igor Shelaputin

Danilovsky Market circa 1975 – Photo by Igor Shelaputin

In the late 1970s, it was decided to give Moscow’s historical markets a new, modern look. Thus began the design of new buildings for the Baumansky, Cheremushkinsky, Dorogomilovsky, Usachevsky, and other well-known markets, including Danilovsky. Most of them were to be covered, making unparsimonious use of the material of choice in the Land of the Workers: reinforced concrete.

This excellent article (in Russian) describes the architecture of the Danilovsky Market in great detail, and I’m providing a summary translation below. The current structure was built in 1986, and the leading inspiration for its design was the dome of the Druzhba Multipurpose Arena, built for the 1980 Summer Olympics and nicknamed “turtle” by Muscovites.

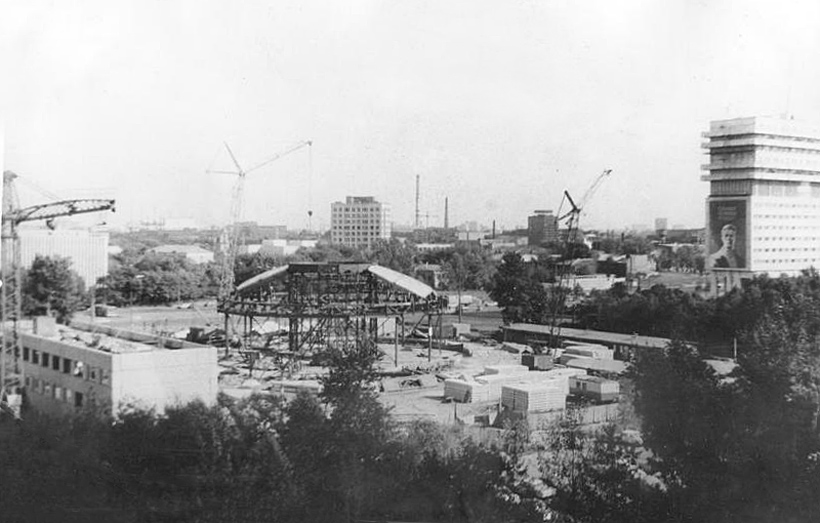

With its elegant dome, the Danilovsky Market became a real embodiment of modernist ideas. Danilovskaya Square, where it’s located, concentrates in a short radius some of the most important examples of all the architectural styles that existed in the USSR. Down Serpukhov Boulevard, the Khavsko-Shabolovsky residential block is an outstanding embodiment of Soviet avant-garde from the late 1920s. Next to it, the Shabolovka radio tower symbolizes hopes for a better life. A bit north of the market, the Danilovsky department store illustrates Soviet “commercial” architecture. The mid-1950s brought modernism, which shaped the image of Danilovskaya Square itself, as it was surrounded by the Moscow Mint (behind the crane on the left, in the picture below) and the 400 meter long “ship-building” (seen on the right, with a propaganda billboard on its side). The square is also a starting point for the Warsaw Highway, along which numerous research institutes are located.

But let’s get back to the market itself. From an engineering point of view, the dome has a diameter of 72 meters, and resembles a flower with 14 petals of reinforced concrete, their tips resting on the ground, and its central disc, 16 meters from the ground, a glass geodesic dome about 15 meters in diameter, necessary for lighting and ventilation. The interior of the market is one bright, large space, with visible concrete in the best tradition of modernism. Complex shaped roofs – with folded, angular, or curvilinear patterns – became one of the main themes of Soviet modernist architecture, as opposed to the Stalinist Empire style, wherein the “fifth” or “upper” facade played no role.

After years of neglect following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Danilovsky Market was fully renovated in 2017, still maintaining its original architecture. But as I started to explain, the role of food markets in the city has changed…

Today, fresh produce, meat, and fish still fill the stalls, albeit in a different setting, and that’s what we’re gonna look at now. (The market also hosts about 30 fast casual eateries, which I’ll keep for my next post.) You can even order food – raw ingredients or cooked meals – online and get it delivered! “Hipster magnet,” says The Moscow Times in a complimentary fashion, praising its impressive renovation and new coolness. “A foodie paradise reminiscent of London’s infamous Spitalfields Market,” marvels Russia Beyond. “Vendors selling the best of Russia and Central Asia’s farm-to-table produce,” comments The Calvert Journal. Let’s get in.

According to Lonely Planet, “The market itself looks very orderly, if a tiny bit artificial, with uniformed vendors and thoughtfully designed premises.” And that’s probably the first impression you’ll get too.

Just look at the old Caucasian man with his stall stacked exclusively with pomegranates. So far, why not? (Never mind how you pay the rent in Moscow by selling only pomegranates.) But to beef up his field cred and prove he’s not a fraud selling somebody else’s fruit imported from India, he has speckled the shelves with a few faded pictures of himself on his lands.

Or see the produce vendor, who doubles up as Caucasian grocer. Want some Borjomi water with your vegetables? No problem! Georgian churchkhela? Sure! Armenian lavash? You got it! Azerbaijani narsharab? Check! I’d be only half surprised if this guy hides plov rice and beshbarmak noodles under the counter, just in case.

These examples also show that seasonal, local produce isn’t necessarily the focus either. My pictures in this post were taken in November 2017, when outside temperatures flirted with the freezing point. Try growing red peppers in a climate like that. And do you remember passing by any orange or mango groves while driving in the Moscow suburbs? If yes, I think you were drunk, my friend. Neither Russia nor any of the former Soviet states produce mangoes in any substantial amount, and Russia’s not too popular for its oranges, either. And asparagus! Asparagus season in Europe: April to June. Russia’s asparagus production is so small, it can safely be rounded down to zero (see my post on LavkaLavka).

It’s not necessarily a bad thing. I love variety, and nobody actually claims that the produce is local, organic, grown in house, or anything else – conveniently, there’s no labeling or other indication of provenance. But I do think that there’s no good reason to go to the Danilovsky Market just to buy any of that stuff (except maybe the pomegranates). As a matter of fact, the number of produce stalls is only a fraction of what it used to be, and usually still is in many other markets.

Now look at the booth of an actual local farmer from Michurinsk, about 400 km southeast of Moscow: garlic, onions, shallots, carrots, butternut squash, white cabbage, dried beans, apples, red currants, dried wild roses, pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, a few jars of homemade sauces… That’s what you can really find in the region at that time of the year. (In a normal place, this wouldn’t have crossed my mind, but here I’m wondering: does the babushka always dress like this, or did she follow the recommendations of her image consultant?)

Then come the pickles: the classic gherkins of various sizes, tomatoes of various colors, cabbage, and carrot. Do I see hearts of palm in the center and kimchi in the back? There’s a watermelon, too! I can’t say I’ve ever tried one, but supposedly, whole watermelons are pickled with salt and water in barrels, and their flesh becomes a bit similar to tomato. At least I’ve discovered something new.

The dried fruits and nuts, as well as the herbs and spices, bring us back to more contrived territory. The displays are pretty and the selection is fine, though again this is a domain where modern supermarkets can compete quite well, apart from their not doubling up as Uzbek souvenir shops selling colorful plates and bowls. Anyway, let me point out a few things that are particular to Russia and its neighbors (especially its neighbors, since Russia isn’t known for its spices): khmeli-suneli (a traditional Georgian blend), a yellow powder labeled saffron (probably as in Imeretian saffron, aka marigold, used in khmeli-suneli), utskho-suneli (blue fenugreek, also used in khmeli-suneli), fenugreek (for basturma and morkovka), wild cumin and barberries (for plov), sumac (for lyulya-kebabs), adjika powder, and dried tomatoes (chopped, to be used more like a condiment; as opposed to sun-dried tomatoes).

Meanwhile, the Mamdeev family offers their organic honey from Bashkiria, and that’s quite an assortment. You can buy meadow or forest honey; honey collected in May (the first of the year) or in the summer; honey from clover, acacia, cinquefoil, fireweed, angelica, 40 plants, linden, chestnut, pecan, or wild flowers. Honey with cedar sap, propolis, or chaga mushroom. And all this without a Bashkir in traditional costume gesticulating with a sword, phew! The Mamdeevs do have a website with an online store, which is a lot more useful.

And now for the departments that went through a real metamorphosis… Starting with the dairy stalls. Yes, you can still buy delicious fresh milk, tvorog, sour cream, or butter. But instead of the usual handful of pedestrian cheeses, there’s a whole selection of imitation Italian (Montasio, Taleggio), and French (Camembert, Raclette, Valençay, coeur de chèvre) cheeses from the four (milk-producing) corners of Russia. I recall that the Raclette was made in Kaliningrad, and I see Camemberts from Lefkadia and Kostroma. For the most part, these newcomers have The Sanctions to thank. Except for the Camembert, perhaps, as Lactalis has been producing similar soft, surface-ripened cow’s milk cheeses for the local market in Russia under the Président brand for many years. It’s no surprise, then, that Camembert has acquired a certain polarity, and is imitated by many producers, some of whom seem also to experiment with their own, potentially more interesting recipes.

The meat section is also unrecognizable, due largely to the fact that following similar butchering charts as the rest of the world (you know, factoring in animals’ muscle placement rather than just chopping your way through the carcass with an ax) has made the meat… recognizable. I’m pretty sure the beef comes from PrimeBeef, the producers of the meat served at the restaurant Voronezh; there’s also a PrimeBeef Bar on the second floor of the market. Even if there’s nothing particularly exciting to the American eye, it’s a brave new world for the Russian clientèle: dry-aged ribeye, tri-tip, chuck roast, picanha (aka culotte)… all in refrigerators, no less.

For a more traditional treat, check out those smoked ducks and chickens!

Moving on to the fish department. Judging by the vendors’ costumes, Russian seafood is fished by sailors, not fishermen. Granted, working in a fisherman jacket indoors all day wouldn’t very comfortable. And anyway, Russia loves its sailors. Russia invaded a country to protect its sailors! Jokes aside, while fresh fish used to be a kind of poor relation in Moscow markets (the closest sea is over 700 km away), there’s now a pretty solid selection. From the Russian lakes and rivers: trout from Karelia, pikeperch, grass carp, freshwater bream, ossetra sturgeon, beluga sturgeon (even in Moscow, this one can’t be that common). From the sea: red mullet, turbot, horse mackerel from the Black Sea, smelt, emperor bream, tuna, cod, seabass from Morocco, seabass from Chile, seabass on sale, and probably more that don’t appear in my pictures. Also squid, shrimp, and rapana. Of all the fish, turbot and Beluga win the palm d’or for most expensive, at $50 per kilo, which is quite a sum in Russia.

The cured fish counter, on the other hand, hasn’t changed much – except for the price of caviar. All the classics are here: salt-cured, hot-smoked, or cold-smoked salmon and sturgeon; pike, salmon, and sturgeon roe; king crab legs; jarred fish such as catfish, pikeperch or crucian carp; marinated herring. And the usual beer snacks: salted and air-dried smelt, freshwater bream, or vobla. There’s also cod liver and sturgeon milt – I gotta remember to try that next time!

The new Danilovsky market is an appealing and quite unique mix. Yes, it sometimes looks artificial, and it would help to tone this down. Maybe create a separate section, where tourists from afar or just around the corner could buy Uzbek plates, take a selfie with a sailor and a babushka, or meet a man who owns real pomegranate trees.

Although the fruits and vegetables are of only marginal interest, many other departments still offer a selection with which only a handful of the capital’s top gourmet stores can compete. Where else can one find pickled whole watermelons, fireweed honey, artisanal Russian cheeses, dry-aged ribeye, smoked ducks, fresh beluga sturgeon, and sturgeon milt? Add to this over two dozen restaurants that manage to avoid turning the market into a museum and help you kill two birds with one stone, allowing you to grab lunch and do your gourmet grocery shopping under one roof. And don’t forget the online delivery service! Jeez, I live in the world capital of everything-delivered-in-less than-two-hours-comma-24/7, so why can’t the Union Square Greenmarket do that?