I know this recipe title is a bit hard to parse. You might be wondering if I’m talking about a new Russian Spring movement aiming to depose Tsar Vlad, or if Lactone is a brand of shampoo. And what is a recipe for Eggs Benny — a quintessential American dish — doing on a so-called Eastern Bloc food blog? Let me explain…

A few weeks ago, I was contacted by the World Science Festival in New York to participate in one of those Man vs Machine cook-offs inspired by the rise of AI in our kitchens. On account of my involvement with Chef Watson, I was asked to play the Machine, or at least the puppet who obeys the Machine, or at least the chef who creates a recipe inspired by data and food science. The organizers wanted to pick a classic American dish, and the contestants would each have to re-invent it in front of an audience within an all-too-short 25 minutes.

There’s only so many times that one can re-invent the burger or even the hot dog. So, as a result of some considerations as to what can realistically be prepared in less than half an hour, a little bit of food history research, and a profound hatred of brunch (that bizarre ritual of the gentry, standing in line for hours just to eat a mediocre plate of eggs) balanced by an enduring desire to elevate my fellow humans’ eating experience, I proposed Eggs Benedict.

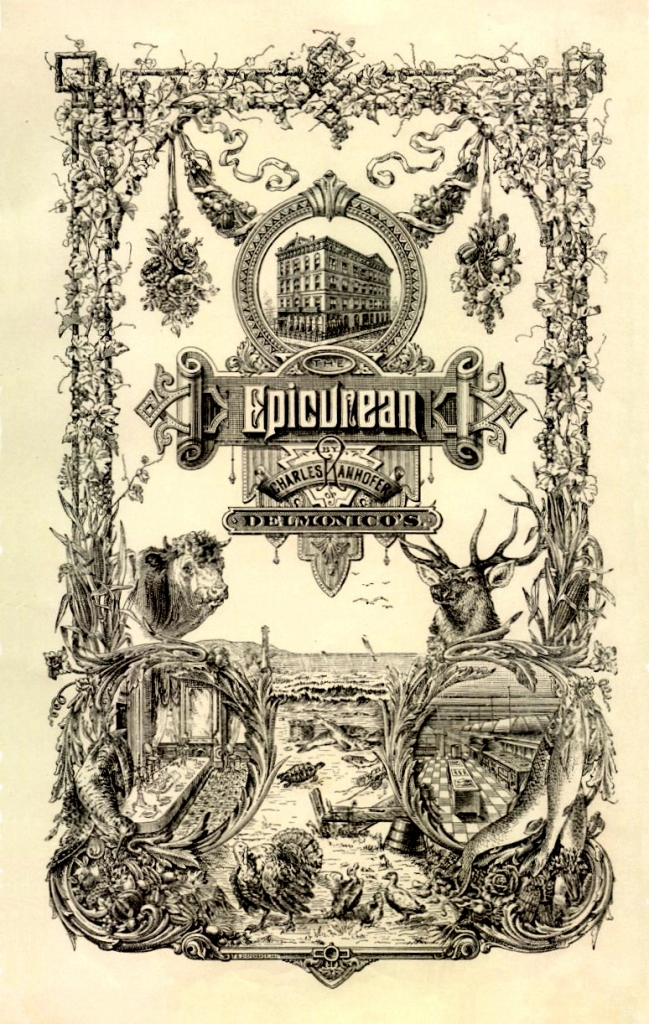

The first recipe for Eggs Benedict can be found in The Epicurean by Charles Ranhofer, then chef at the famous Delmonico’s Restaurant in New York City. Ranhofer was hired in 1862, and under his direction the business was so successful that from 1865 to 1888 it expanded to four restaurants of the same name. Quite naturally, a cookbook followed, wherein the chef published recipes from his tenure of over 30 years. Recipe No. 2925 reads:

POACHED EGGS A LA BOELDIEU AND EGGS A LA BENEDICK (Oeufs Poches a la Boeldieu et Oeufs a la Benedick).

[…]

Eggs a la Benedick. Cut some muffins in halves crosswise, toast them without allowing to brown, then place a round of cooked ham an eighth of an inch thick and of the same diameter as the muffins on each half. Heat in a moderate oven and put a poached egg on each toast. Cover the whole with Hollandaise sauce (No. 501).

The “Eggs a la Boeldieu” was a pretty different recipe that Ranhofer decided to group under the same header, for no apparent reason. The cookbook, like many of its contemporaries, lists hundreds of eggs recipes. Just change one single ingredient, and you get to name the dish something else.

Did Ranhofer invent Eggs Benedick? We don’t know, but it’s entirely plausible. Today, Delmonico’s (which stopped being operated by the Delmonico family long ago, and now has a new life under the management of a Croatian-American family) claims on its menu that Eggs Benedict (now spelled with the T) was “created at our stoves in 1860” — a gratuitous and rather doubtful statement that would suggest the dish predates the Ranhofer era.

Still, there seems to be no mention of the Benny in cookbooks prior to Ranhofer’s. The next recipe appears in another American classic of the time, Fannie Merritt Farmer’s Boston Cooking-School Cook Book, published in 1896:

Eggs a la Benedict

Split and toast English muffins. Saute circular pieces of cold boiled ham, place these over the halves of muffins, arrange on each a dropped egg, and pour around Hollandaise Sauce II (see p. 274), diluted with cream to make of such consistency to pour easily.

Benedick has already become Benedict here, but we don’t know why — just a more popular name, maybe. From there, in any case, the recipe spreads quite rapidly, and by the early 20th century it can be found in lesser cookbooks, sometimes bastardized by way of replacing the English muffin with toast.

There are many other diverging stories on the origins of the dish. All of them seem to agree, though, that Eggs Benedict was invented in New York.

First, there’s the December 19, 1942 issue of The New Yorker. In a short article dedicated to retired stock broker Lemuel Benedict, we are told the following:

Forty-eight years ago Lemuel Benedict came into the dining room of the old Waldorf for a late breakfast. He had a hangover, […] ordered some buttered toast, crisp bacon, two poached eggs, and a hooker of hollandaise sauce, and then and there proceeded to put together the dish that has, ever since, borne his name.

But you can always count on journalists, even in major publications, to prefer an entertaining story to boring, fact-checked reality. This version places Lemuel Benedict’s Aha! moment one year after the publication of The Epicurean, a date which makes it pretty clear that he can’t have invented the dish. The ingredients aren’t even the same, so the article calls Oscar of the Waldorf to the rescue to replace the toast with English muffin and the bacon with ham (why he’d do that, we don’t know). Since the article also mentions that Lemuel was a regular at Delmonico’s, I’m inclined to rewrite the story as follows:

One late-morning in 1894, a disoriented Lemuel Benedict, suffering from a severe hangover after the kind of night of excess for which Wall Street is infamous, wanders into the dining room of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. But does he really know where he is? In his drunken stupor, and because there’s nothing that looks more like a high-end restaurant than another high-end restaurant, he thinks he’s at Delmonico’s, another of his favorite hangouts. He even recognizes the maître d’hôtel, Oscar Tschirky. So he orders his usual hangover cure: Eggs Benedick, a recent creation from chef Charles Ranhofer, that piles up enough fat and carbs to flush the alcohol out of anybody’s bloodstream. Maybe he even slurs the name a little or confuses it with his own name. The maître d’, slightly nonplussed, explains to him that there is no such dish on the menu, and that he no longer works at Delmonico’s but now runs the Waldorf’s dining room, where they are right now. At this moment, Benedict realizes that he’s in the wrong restaurant, but like any good stock broker, he’s not gonna lose face in front of some turncoat waiter. Of course he knows there’s no Eggs Benny on the menu, but he wants it anyway! Collecting his memories of Eggs Benedick, he adapts the ingredients: toast (he never really liked English muffins), bacon (isn’t it English bacon they put on those English muffins at Delmonico’s? and isn’t that basically the same as ham?), poached eggs, and hollandaise on the side (too much hollandaise makes him nauseous, and a true New Yorker always asks for one of the key ingredients on the side). The story could have stopped here, but like any good stock broker, Lemuel Benedict has a big mouth. He frequently has guests at his house, and isn’t even afraid to put on an apron every once in a while. Already an influential man, he sees a unique opportunity to add a rare feather to his cap; how many people are still alive to claim they invented a dish that now bears their name? Forget about Eggs Benedick, here come Eggs Benedict! As the years pass, he embellishes his story and repeats it to half of New York’s beau monde, so much so that, eventually, one the most esteemed magazines of the time publishes it without ever questioning its veracity.

Then, there’s Craig Claiborne’s September 24, 1967 New York Times article. Claiborne, a food critic, tells us a rather bizarre story speckled with some questionable statements such as “Eggs Benedict is conceivably the most sophisticated dish ever created in America.” Supposedly, one Edward P. Montgomery, an American living in France, wrote a letter to the Times purporting to reveal the genuine Eggs Benedict recipe because “he cringes at the thought of what passes for the dish in most Americans restaurants.” Even though Montgomery could surely distract himself with a variety of culinary delights on the other side of the Atlantic, the thought of the dire situation in his homeland is so unbearable to him that he has to write a letter to the media in hoped of restoring the truth, of which he is the sole keeper. In addition to providing The True Recipe, he reveals that Eggs Benedict were invented by Commodore E.C. Benedict, a prominent New York banker and yachtsman (it’s amazing how many rich New Yorkers love to invent egg dishes). How does Montgomery know? Get ready for this: he received the recipe from his mother, who had been given it by her brother, who was a friend of the Commodore. (In Montgomery’s adoptive country, there’s a proverb: l’homme qui a vu l’homme qui a vu l’ours, the man who saw the man who saw the bear.)

There are several problems with this story. At the very least, it sounds more plausible that Commodore Benedict, who probably ate at Delmonico’s in the late 19th century, and certainly must have eaten at other restaurants serving Eggs Benedict later on, simply tried Eggs Benedick / Benedict at some point, and asked his cook to reproduce the recipe. Maybe he suggested a few tweaks (the recipe given in Claiborne’s article mentions a somewhat unconventional hollandaise with ham trimmings) and then jokingly renamed the result after himself before passing the recipe along to his friends. There’s also the fact that the recipe calls for an electric blender: Benedict died in 1920 and the the electric blender was invented in 1922. Of course, the recipe could have been rewritten later to provide a simpler way to make a hollandaise… But the recipe could also be a hoax altogether. After all, there are several ways to get mentioned in the media: A) be famous, B) commit a crime, C) do something out of the ordinary whether for its brilliance or stupidity, or D) make up a story about any of the above.

But it’s time to get back to my own recipe. Which I really did invent myself! And which isn’t a hoax! One of my missions as an AI evangelist is to explain that AI is there to advise, not replace, humans. To present AI as Augmented, not Artificial, Intelligence. So I wanted to create a recipe that would use data and food science, but still shows my personal style and a sense of time and place. I chose ingredients that all occupy a place in Russian cuisine: buckwheat blood sausage, scallops (which nowadays are fished in the Murmansk region and in the Peter the Great Gulf; more on trending Russian seafood in another post), ramsons / ramps, porcini (called simply white mushrooms in Russian), rye bread, nuts, and dried fruits… And at least some of these ingredients have a strong seasonal (the ramps, the porcini) or local (the scallops, the blood sausage, the ramps) identity.

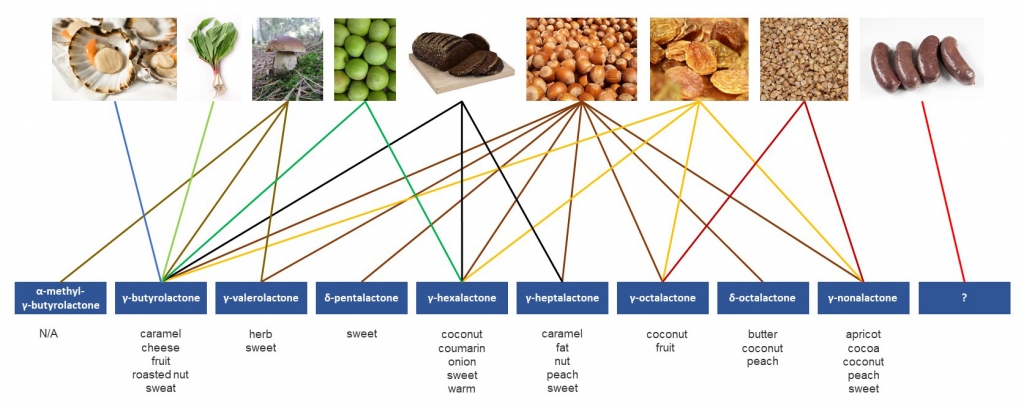

For the science part, I tried to create a compelling example of foodpairing. I consulted the database of Volatile Compounds in Food, which lists the flavor compounds contained in the most common ingredients, as well as a couple of books that present some of the same information in a more digestible format for chefs: James Briscione’s The Flavor Matrix, and François Chartier’s L’Essentiel de Chartier. I knew I wanted to include some seafood, so I started looking at the ingredients that pair well with crab, shrimp, scallops, and the like, focusing on the ones present in Russian cuisine. After some research, a pattern slowly emerged around a family of aromatic components called lactones. Lactones contribute to the aroma of butter, cheese, fruits, and various other foods; they’re also found in wines aged in oak barrels, especially Chardonnay. The beauty of lactones is that even if ingredients contain different compounds from the family, using all these compounds together creates a great flavor synergy.

With a little bit of work, I created a recipe in which all the ingredients contain lactones, and I’ve summarized all the connections via chart (see below). The ingredients at the top are connected to the different lactone compounds they contain, and I’ve added some flavor descriptors for each compound (all this data comes from the database of Volatile Compounds in Food). I separated my buckwheat blood sausage into buckwheat and blood sausage; Chartier mentions that blood sausage contains a lot of lactones (so does pork), but doesn’t provide the compound names, and neither do my other sources; hence the question mark on the chart. Porcini and blood sausage also share a non-lactone compound, 1-octen-3-one, which is responsible for the metallic smell of blood.

The recipe isn’t just a complex mix of flavor compounds, however. I also made sure to balance sweetness (the raisins), sourness (the hollandaise), saltiness (most ingredients) and bitterness (the mustard micro-greens), with a good dose of umami from the sautéed scallops. And the green hollandaise made with the ramp leaves adds exceptional visual appeal. The result? Delicious! The other contestant simply has no chance! I’ll follow up once the World Science Festival publishes the video of the competition, but in the meantime, you can already try the recipe at home.

Ramp green hollandaise

Yields slightly over 2 servings

65 g Champagne vinegar

30 g peeled shallots, thinly sliced

110 g (about 3) egg whites

50 g butter, sliced

40 g milk

4 g salt

12 g lemon juice

20 g ramp greens

1 g xanthan gum

- Combine the vinegar and shallots in a small saucepan, and reduce by half over high heat.

- Strain the vinegar reduction, and weigh 25 g of the liquid, discarding the rest.

- Place the vinegar reduction, egg whites, butter, milk, salt, and lemon juice in a sous-vide pouch. Cook in a 75 C / 167 F water bath for 25 minutes.

- Blanch the ramp greens in boiling water until soft, then drain on paper towels, and reserve.

- Transfer the contents of the pouch to a blender, add the ramp greens and xanthan gum, and blend on medium speed for 1 minute.

- Transfer to a 1 liter siphon, and charge with two cartridges of N2O. Shake several times, then reserve in a 65 C / 150 F water bath until serving.

Preparation for first egg

Yields 2 servings

15 g ramp whites, sliced

80 g porcini, cut into thick slices

20 g golden raisins

20 g butter

20 g water

salt

black pepper, ground

- Place the ramp whites, porcini, golden raisins, butter, and water into a small saucepan, and season with salt and pepper. Cook over medium-low heat, stirring occasionally, until the mushrooms are tender.

- Remove from heat and reserve in a warm place.

Preparation for second egg

Yields 2 servings

40 g buckwheat blood sausage

canola oil

50 g cleaned bay scallops (or regular scallops cut into large dice)

salt

black pepper, ground

10 g peeled Granny Smith apple

- Place the blood sausage in a sous-vide pouch, and heat in at 65 C / 150 F water bath for about 20 minutes.

- Heat some canola oil in a pan over high heat. Season the scallops with salt, then sauté until brown on all sides, without overcooking them. Drain on paper towels, season with black pepper, and reserve.

- Cut the apple into a fine brunoise, and reserve.

Assembly

Yields 2 servings

20 g hazelnuts, coarsely chopped

salt

4 slices pumpernickel rye bread, cut into 8 cm diameter discs

15 g butter

4 very fresh large eggs

preparations for first and second eggs

mustard micro greens

- Toast the hazelnuts in a pan over medium heat until slightly colored, then season with salt, and reserve.

- In the same pan, toast the bread on both sides with the butter. Reserve.

- Bring a medium pot of salted water to a boil, then reduce the heat to low.

- Taking one egg at a time, break each egg into a small bowl. Swirl the water in the pot using a rubber spatula, and pour the egg into the pot. Poach for 4 minutes, stirring the water occasionally. Take the egg out with a slotted spoon or a skimmer, and drain on paper towels. Repeat with the 3 remaining eggs.

- Take the blood sausage out of its pouch, and remove the skin.

- On each plate, place two slices of toasted bread.

- On top of the first slice of bread, arrange some porcini slices into a single layer. Place one poached egg on top, then add on a bit of the ramp-raisin mixture. Cover with hollandaise, and add more ramps and raisins.

- On top of the second slice of bread, spread some blood sausage. Place one egg on top, and add some of the scallops. Cover with hollandaise, then add more scallops and the apple brunoise.

- Sprinkle all the eggs with hazelnuts, and finish with some mustard micro-greens.