I’ve been wanting to write about Georgian wines for quite a while now. First I promised I would include a chapter about Kakheti wineries in my Georgian Adventures series, and completely forgot about it (I’ll fix that soon). Then I started buying Georgian wines and jotting down tasting notes about them, but felt like a post with pictures of bottles and wine glasses on a side-lit wooden board wouldn’t elicit much more than a yawn.

Yet there would be much to write about, as Georgian wine is trending, and with good reason. It used to be that all one could find in the US (and other markets) was the mass-produced stuff. Some producers wagered that European production methods would bring them recognition, not realizing that few Americans will buy wines from a country that they don’t know if it tastes like something that could come from pretty much anywhere, and doesn’t even cost less. Other producers were just happy to sell sweet plonk in kitschy clay vessels, the containers probably worth more than the contents. But in recent years, the wine critics of the world have discovered Georgia’s unique winemaking traditions, wherein natural wines are made in large clay amphorae called qvevri. UNESCO included this method of wine production on their list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2013. Many of these interesting wines are now being imported to the US — I just needed the right opportunity to introduce them.

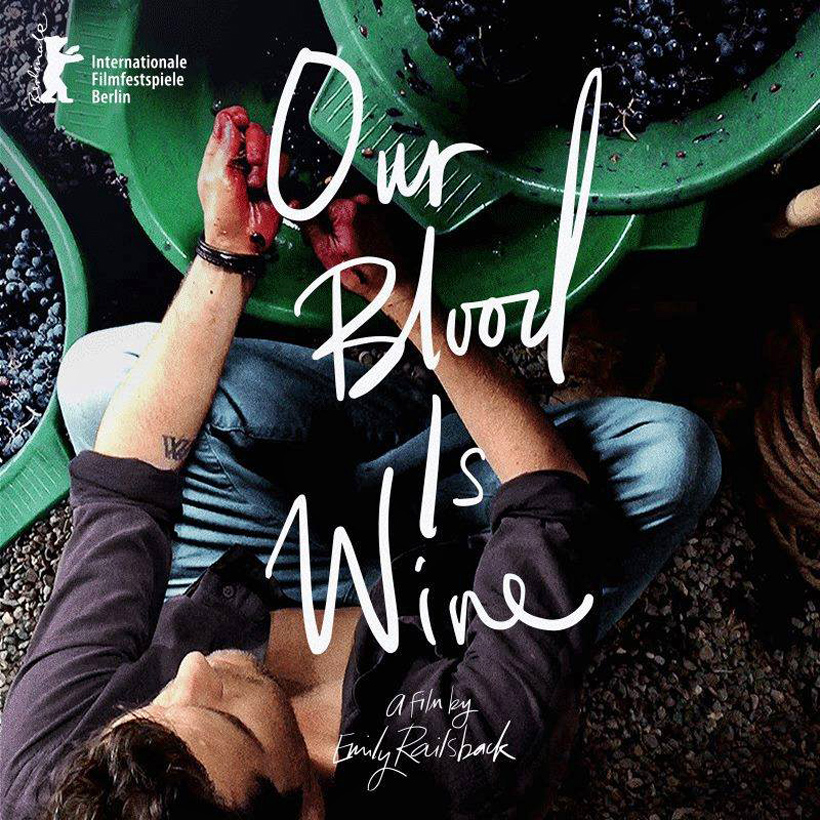

Enter the National Wine Agency of Georgia and the event that they organized last week in New York City, which I had the opportunity to attend: a screening of Our Blood is Wine, a just-released documentary on Georgian wine, followed by a tasting of wines from several producers (at Ten Bells on the Lower East Side) and a presentation/book-signing for Carla Capalbo’s Tasting Georgia: A food and wine journey in the Caucasus, a travel guide cum qvevri-loving wine guide cum cookbook. Quite a combo!

I wholeheartedly recommend both the documentary, which follows the peripatetic journey of sommelier Jeremy Quinn meeting with qvevri makers and small wine producers, and Carla’s book, which collects into a single elegant tome the sort of multi-disciplinary information (food, wine, travel) that I usually seek when preparing for a trip. But I’ll let you discover them on your own — the documentary can be viewed in select theaters or on VOD, and the book can be bought wherever books are sold. While you’re at it, you could also look Otar Ioseliani’s Falling Leaves, a Georgian film from the sixties about coming-of-age, wine, the Soviet Union, rampant carelessness, and corruption. Meanwhile, I’ll be talking about Georgian wines, at last!

Now a word about those qvevri. Qvevri are large earthenware vessels used for the fermentation, storage, and aging of traditional Georgian wine. If you enjoy looking at old pots, you can admire ancient qvevri (some up to 8,000 years old) at the Georgian National Museum. (You also see quite a few of them in Our Blood is Wine, as well as learn about how they’re made.) If you want to find out more, an entire short book on the subject is available here in PDF, from the Georgian Wine Association.

The winemaking process is quite simple. First, the grapes are pressed, which produces the juice on one hand, and the pomace (a mash of pips, skins, and stalks) on the other. Then the juice and the pomace are fermented and aged in the sealed qvevri, where they typically stay for three to six months. Finally, the wine is decanted and bottled. No yeast, no additives; very natural indeed. Many variations exist, the most famous ones named after the regions where they were traditionally used: the Kakhetian method, the Imeretian method, etc. The differences reside in the amount of pomace mixed with the juice (from all of it, to skins and pips only, to none), and in the duration the pomace stays in contact with the wine (through fermentation only vs. through both fermentation and aging). Winemakers can also play around with the total time the wine spends in the qvevri (three months, six months, more), as well as the way the qvevri is stored (buried, above ground, indoors, outdoors).

Qvevri and Qvevri Wine Museum in Napareuli, Kakheti

A few years ago, less than one percent of Georgian wines were produced in qvevri. All the wines I’ll talk about next are, though. The event at Ten Bells wasn’t a formal wine tasting so much as a very crowded night at a bar, where several Georgian wines were available by the glass, so I couldn’t try everything on offer — here’s a small selection, starting with a couple wineries off the beaten path…

Mariam Iosebidze is one of very few female winemakers in Georgia. A guide for a travel agency by day, she began making wine in 2014, using her uncle’s marani (wine cellar) in the mountains just south of Tbilisi. With 600-700 bottles of organically farmed Tavkveri every year (an indigenous red varietal from the region), she’s one of the smallest producers of traditional natural wines in Georgia.

Mariam’s wine label bears her name, as is the case with many small producers. Her Tavkveri 2016 was recommended to me by Jeremy Quinn, the sommelier whom we follow in Our Blood Is Wine, as a wine that challenges preconceptions. The official tasting notes from Georgia’s National Wine Agency describe it as follows: “Refreshing and expressive, aromas of sandalwood incense, white pepper, and plenty of fresh red fruit. Tart cranberries, green strawberries, and bay leaf swirl across the palate.” Though I won’t pretend to have identified more than half of the above flavors (cranberries and bay leaf, OK, but do green strawberries have a smell?), this is indeed a fairly light, fruity red, but with the tannins and cloudy appearance characteristic of a natural wine. An interesting wine that will probably benefit from a couple years of aging to soften the acidity and tannins.

Ramaz Nikoladze is the head of Slow Food in Georgia. He started Nikoladzeebis Marani (Nikoladze Wine Cellar) in 2007 on the location of his great-grandfather’s vineyard and cellar, in the village of Nakshirgele in the Imereti region. His 80 acres are planted with two indigenous white varietals, Tsitska (found almost exclusively in Imereti) and Tsolikouri (also from Imereti but now planted throughout Georgia and beyond). Ramaz only makes around 3,000 bottles per year, and is also the co-owner of the Vino Underground wine bar in Tbilisi.

Ramaz’s Tsolikouri 2016 is amber-colored and clear. The official tasting notes read “exotic notes of spice, apricots, and tea producing a finely tannic, elegant finale.” I mostly get the apricot nose, and again the finish characteristic of qvevri wines. Call me a walking cliché if you like, but I wish I could try these wines with Georgian food, such as a proper Imeretian khachapuri. The diminutive selection of Georgian small plates offered at Ten Bells at this event, consumed via careful gestures in a vain attempt to avoid elbowing one’s neighbors, is a poor substitute.

And now for Kakheti, Georgia’s most famous wine region (even though pretty much every part of Georgia makes wine). Pheasant’s Tears Winery is located in the very photogenic village of Sighnaghi. It was founded in 2006 by Gela Patalishvili, a Georgian winegrower, and John Wurdeman, an American with a passion for painting and music, a degree in Fine Arts from the Surikov Art Institute in Moscow, and a fascination for Georgia’s rich food and wine culture. The winery offers a broader selection than the smaller producers, and focuses on the rarer varieties and terroirs of Georgia, organically farming vineyards in various regions. No pheasants are harmed in the making of their wines — their name comes from an old Georgian folk tale in which only the best wines could make a pheasant cry tears of joy. John also owns several wine-focused restaurants, and founded Living Roots, a wine tourism company focused on the wine, food, and culture of Georgia.

Pheasant’s Tears’ Rkatsiteli rosé 2016 hails from Tibaani in Kakheti. Natural rosé wines and Rkatsiteli rosés are both rare, so a combination of the two is rather unique. The cloudy wine boasts a potent berry nose (strawberry in particular), and I’ve seen some people mention walnut and wildflower honey as well. What I consider the typical acidic and tannic finish of natural wines is there, but restrained. If you ask me, this is how every rosé should be. A kind of punch in the nose to all the sheeple who enjoy drinking bad rosé all summer because marketing says it’s so refreshing.

Okro’s Wines, John Okruashvili’s winery, is also located in Sighnaghi. John’s had a tumultuous career, having started out at the University of Southampton writing computer programs for physics experiments, followed by a stint as a telecoms network consultant in Baghdad. John then returned to live in Georgia and has been bottling his own wine since 2009. His vineyards are located at cool, high altitudes, making his wine full of vitality and freshness while also being quite concentrated. He also likes to produce chacha (pomace brandy), and owns a restaurant.

Okro’s Wines’ Saperavi 2016 is a classic natural Saperavi, another indigenous red, is something that every Georgian wine neophyte should try (although I must say I prefer the whites and rosés). The tasting notes, this time coming from the producer’s own website, are succinct: “observed with nice aroma of fruits and the harmonic taste.” I agree. Apparently London’s Yotam Ottolenghi loves drinking this wine with roasted eggplant, and Ottolenghi knows a few things about roasted eggplant (How do I know this? I have grossly generalized and distorted what I read here). Add another Georgian touch and try it with my walnut-stuffed eggplant rolls.

The wines from this event, as well as others, are imported by Terrell Wines (read about Chris Terrell here). They’re generally in the $20-30 price range, which is super affordable for natural wines — some Italian winemakers purchase Georgian qvevri and make wines that sell for at at least double that price. Chambers Street Wines caries Mariam Iosebidze’s wine. Vineyard Gate sells an older vintage of Ramaz Nikoladze’s Tsolikouri, which should be interesting to try. Astor Wines and 67 Wine both have various wines from Okro’s Wines and Pheasant’s Tears. K&L Wine Merchants has a smaller but worthy list, including several wines from Pheasant’s Tears. Blue Danube has a pretty large selection, from natural wines to less recommendable mass-produced stuff, though none of the wines I’m writing about here. Since the production is very small, the wines on offer are likely to change often..

There’s a lot being written about Georgian wines right now, and you have more options than ever if you want to try them for yourself — from traveling Georgia’s constantly improving roads to visit local producers, to tasting the wines in the comfort of a restaurant or wine bar in Tbilisi (or Sighnaghi, or New York), to buying some of those wines online and reading Carla Capalbo’s Tasting Georgia on your couch. If you opt for the latter, don’t forget to play some Georgian polyphonic songs with that!

Thanks to Christine Deussen for organizing the event and for providing most of the pictures in this article.

1 comment

Great post. Love Georgian amber wines and had hoped to find them back in Australia- unfortunately it’s proving difficult. Fortunately however, there are quite a few Aussie winemakers taking a turn at natural wine making, some even using concrete eggs in place of qvevri. Petnat in particular is becoming very popular.