Throughout Europe and perhaps even more so in Eastern Europe, various herbal liquors have long been invented and consumed for their medicinal properties. Chartreuse, whose recipe originates from a mysterious 17th century manuscript, began its commercial life at the pharmacy of the Grande Chartreuse monastery in 1737. In Latvia, in 1752, a pharmacist named Kunze crafted the famous Riga Black Balsam recipe, and 16th century records from other Riga pharmacists mention earlier herbal elixirs. Hungary’s Unicum was created in 1790 by Dr. József Zwack, in his capacity as Royal Physician to the Imperial Court, and was originally prescribed as an aid for indigestion. Becherovka debuted as a kind of digestive medication in the early 19th century, at Josef Becher’s pharmacy. Bénédictine was created in 1863 by wine merchant Alexandre le Grand, with the help of a pharmacist and using old recipes from the Abbey of Fécamp.

Karelian balsam, on the other hand, stands out as an exception. While it can’t be ruled out that people in Karelia might have used local herbs, roots, and berries to infuse alcohol for quite some time, or asserted the occasional curative virtues of their concoctions, the region does not claim any traditional recipe for balsam – a name given to any Northeastern European herbal liqueurs with a high alcohol content, like Latvia’s popular beverage. Instead, Karelian balsam was invented almost out of the blue at Petrozavodsk’s Petrovsky Liquor Factory, in the 1970s, under the direction of one V. A. Tripetskaya.

Tripetskaya worked at the factory for more than 40 years and was its director for over a quarter of a century, from 1971 to 1997. During her tenure, she co-invented many of the beverages created there. If you remember my post on Petrovsky’s history, the late-1960s and early-70s saw a period of modernization and innovation. Around the same time, the factory started expanding its product range. They were already producing some alcoholic beverages off the beaten path, such as the Petrovskaya vodka flavored with breadcrumbs, or a liqueur made with rowanberry and cognac, but these weren’t their recipes. They wanted to create something they could call their own, while focusing more on local, high-quality ingredients. Instead of making another spirit infused with berries (of which there was undoubtedly no shortage), they decided to set the bar higher and make a balsam. A Karelian balsam would achieve three objectives at once: demonstrate the factory’s mastery of alcoholic beverages, use a variety of local products, and include ingredients with healthful virtues. This last point being a callback to herbal liqueurs’ original function, and also the kind of thing that Russians would appreciate (in a country then plagued by alcoholism, nobody would pass up a chance of getting drunk in the name of good health).

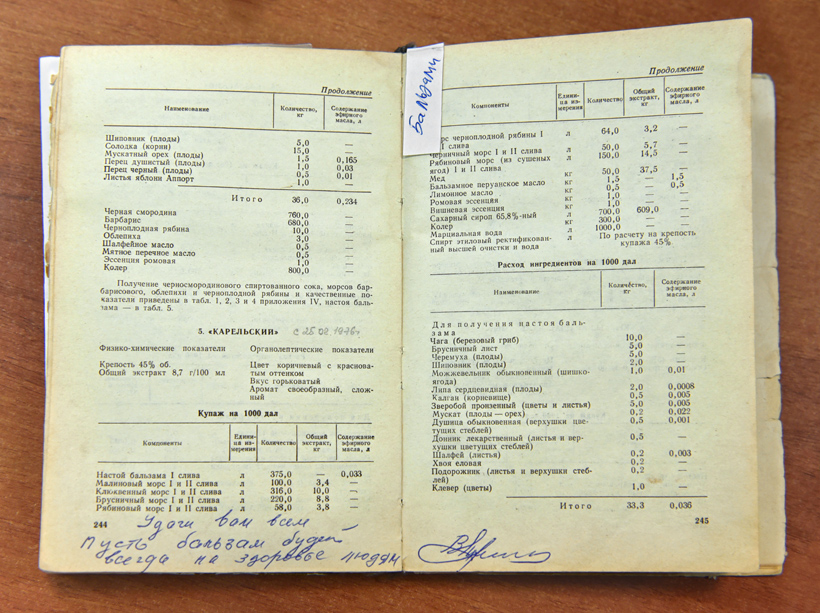

Because it involved not two or three ingredients but over thirty, creating the recipe took nearly two years. The final product included Karelian berries, medicinal herbs and roots, and even a unique, highly mineralized water – the same as the one I mentioned in my previous post on how vodka is made. Of course, the balsam had to be approved in Moscow, where it didn’t sit too well that a provincial factory had created its own balsam when the USSR already had the one and only Riga Black Balsam. Still, in 1976, approval came through for the registration of Karelian Balsam. As a result, the recipe would be included in the repertoire of classic alcoholic beverages used by Soviet factories to create their product lines (the selfsame Retseptury likero-vodochnykh izdelii i vodok that I used in that vodka post). To this day, Karelian balsam remains Petrovksy’s pride, a now-traditional liqueur sought after by tourists from Russia and abroad (well, okay, mostly from Russia).

Making Karelian balsam is a pretty complex process. It all starts with collecting the long list of ingredients, which fall roughly into three categories (the complete recipe is at the bottom of this post):

- an arcane mix of fourteen plants (leaves, flowers, roots) and one mushroom, selected partly for their medicinal properties and partly for their availability in the region, macerated together in alcohol to form the so-called “balsam” infusion (3.75% of the final product, but packing a potent flavor)

- berries, seven different kinds, from raspberries to cranberries to rowanberries, most of them fresh but some dried, also infused in alcohol (the seven berry infusions together account for almost 10% of the final product)

- a handful of ingredients that are mixed together with the above infused alcohols when the balsam is assembled, including a few essential oils and essences, honey and sugar syrup, alcohol, and water.

Most of the berries and plants can be found in Karelia. In the beginning, factory workers used to go out and gather the berries and plants themselves, but as production increased, these things had to be bought in. Now, the berries (all organic) still come from the region, but some of the other ingredients are sourced from further afield.

The plants (and mushroom), are left to infuse for an entire month so that their essential oils and pectic substances can be fully extracted. It takes a whopping 33.3 kg of raw materials, plus 500 liters of a mix of alcohol and water with a 50% alcohol content, to produce the 375 liters of “balsam” infused alcohol that the canonical recipe of 10,000 liters of final product calls for.

The berry-infused alcohols (called mors; the same name as the non-alcoholic berry cocktail made with berries and water) take slightly less time. Each kind is processed separately, following slightly different recipes that call for different amounts of fruits and different alcohol proofs – all of which are standardized in the aforementioned Retseptury likero-vodochnykh izdelii i vodok. The overall process, however, remains the same. Except for the dried rowanberries and bilberries, the berries arrive frozen and get thawed at the factory. Why? Because this freezing and thawing makes the skins burst, which later facilitates the transfer of the pectic substances and flavors into the mors. For much of the same reason, most of the berries, excepting the softer ones such as raspberries, are crushed.

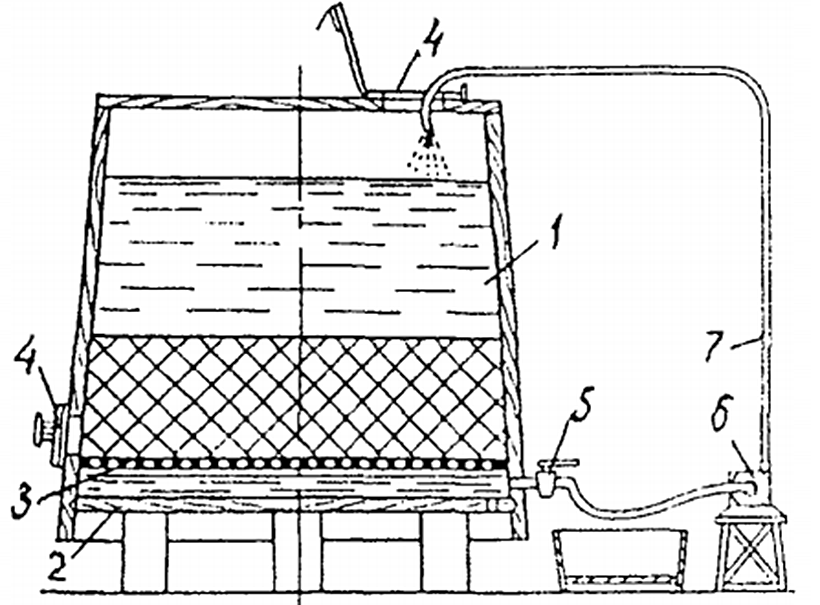

Next, everything goes into a special vat with a false bottom that serves as a sieve: the berries remain on top of the false bottom, an alcohol-water mixture (the alcohol content generally ranging between 45 and 60%) is poured into the vat, and the alcohol trickles through the berries and the false bottom. A faucet is placed between that false bottom and the “main” bottom, so that the infused alcohol can be drained out while keeping the berries in the tank.

The berries are infused that way over seven days, with periodical stirring (in the above illustration, stirring is achieved by taking infused alcohol from the bottom and re-injecting it at the top of the vat; the pipes I saw at Petrovsky suggest that this is how they do it too). After a week, the liquid is drained from the tank (while the berries stay in the vat, on account of the false bottom), and this first run produces a very bright mors. There’s still more flavor to be squeezed out of the berries, which justifies a second run. So the vats are refilled with alcohol (generally less, about 70% of the amount used in the first run, and with a lower alcohol content at 30-35%) and the process is repeated for another seven days. We now have a first run and a second run mors for each berry. The factory has a room full of these vats with false bottoms, used to make all the different berry infusions, together with tanks used for the balsam infusion. Ultimately, to produce the 958 odd liters of berry-infused alcohol of the 10,000 liter canonical recipe, it takes about 382 kg of berries.

Once the maceration is over, the mors goes through a filter press for a first filtration. Then it’s stored in a cold chamber at -18 C for two weeks, brought to +3 C to thaw, and filtered again. The goal of this freeze-thaw cycle is to help separate the pectic substances that could eventually create a deposit in the final product.

We’re now headed to the blending department – time to put all the ingredients together! The various berry mors (both 1st and 2nd runs) and the balsam infusion are combined in the proportions specified by that official Karelian balsam recipe, and mixed with agitators. Then the honey (heated to be more liquid), caramel (made on the premises and used both for color and flavor) and sugar syrup are added, then the rectified alcohol and water, and finally the other natural flavors (essential oils and essences).

The final product goes to the lab for testing 4 or 5 times, and corrections are applied iteratively based on the results of the tests, to adjust the alcohol content, extract content, sugar content, and/or acidity. And then there’s one more filtration, to reach the desired shine – when you hold the balsam by a light source, it must shine and elicit oooohs and aaaaahs of admiration. This filtration consists of a filter press with cardboard filters between each plate, the liquid cycling through under pressure.

And that’s it! The balsam goes into tanks to rest briefly and wait to be bottled. The total production takes about 45 days. Although it hits store shelves quite shortly after that, if you purchase a bottle, it’s recommended that you wait a bit before opening it: the longer the balsam stays in the bottle, the more time the ingredients have to blend, so the mix becomes better rounded. However, since balsam is a natural product, it does have a finite shelf life. Balsam’s expiration date is set to 12 months after production (which you can push back a little if you store it in good conditions), after which it has a tendency to become cloudy and form a deposit. And by the way, you should not keep balsam (or berry-infused vodka) in the fridge – ideally, it would be kept at about +10 C.

For the past 40-plus years, there’s been only one Karelian balsam. But this may be about to change, as the Petrovsky Liquor Factory is working on three new flavor variations: blackcurrant, cherry, and prune. (They are certainly drawing inspiration from the Riga balsam, which is now available in blackcurrant and cherry.) In fact, back in the lab, some samples were being assembled at the time of my visit. While the original balsam contains 45% alcohol, its flavored siblings will be milder, at 35% or 40%, and obviously, each one will have a dominant flavor note, which is missing in the original balsam.

So. If you follow my blog regularly, you must know I’m actually not all that crazy about herbal liqueurs – see my post on Becherovka, for example. I’ve actually talked about Karelian balsam once, years ago, when I was discussing vodkas from the Vanished Empire. I called it an “abomination,” but with my newfound knowledge I can see that the decades-old bottle I was drinking from at the time was certainly at fault (remember: one-year shelf life). It’s time for a more rigorous tasting…

The main differences between Karelian balsam and Riga balsam are that the former contains more sugar, while the latter contains more medicinal plants that give it – get ready for it – a medicinal, bitter taste. Or, to quote the Petrovsky Liquor Factory leadership, “you can actually drink the Karelian balsam.” However, they don’t recommend drinking too much of it either, as its high herbal content can get you into a kind of “excited” state, where your heart starts beating with “more intensity.” (Oh no, we wouldn’t want to be in an excited state; we’d much rather drink plain vodka, a spirit with a lower alcohol content, a neutral taste, and barely any aftertaste!)

If you want to fully appreciate the complexity of the plant and berry blend that makes Karelian balsam, it’s recommended that you have it on its own (and neat, unlike what’s shown in the marketing photo further down below). At Petrovsky, we poured it in the same tulip-shaped glass that we used to taste vodka, but the traditional Glencairn whisky glass works great too. When you swirl it in a glass, the dark mahogany color is less intimidating, more like a rich brown with golden and reddish hues. The nose is actually quite pleasant, if hard to define: the mixed berries are there, giving it a slightly jammy quality; I detect notes of caramel and dried fruits (such as raisins, even though there are no raisins) which my brain associates with sweetness and richness; I can easily tell the alcohol content is higher than in a liqueur; I barely smell the herbs. Asked what they thought the predominant flavor was, my hosts shared the opinion that it’s hard to identify the individual components of the blend, and that the plant extract is well assimilated with the rest. In the mouth, the sugar does a good job keeping the bitterness of the herbs in check, but I wish it wasn’t as sweet (but then it would have to be less bitter, therefore less herbal, and eventually it wouldn’t be a balsam at all). Overall, it turns out I quite like this balsam. I do agree with the assessment that one can actually drink it, but to me it would also be a great ingredient in a cocktail – more on this later!

Not all the mors made at the Petrovsky Liquor Factory goes into balsam. The factory produces a whole range of natural berry liqueurs (18% alcohol): lingonberry, cranberry, and even cloudberry (something you don’t see often elsewhere). To make 10,000 liters of infused vodka, they use over 2 tons of berries, sugar (270 g per liter) and a bit of citric acid if needed, but no extra coloring. (Should you want to make your own, I think you’d get very similar results by combining equal amounts of berry preserves and vodka, letting the mix sit, then filtering it). I like the ligonberry liqueur, but I have a soft spot for the cloudberry, which perfectly captures that berry’s elusive creamy taste. Cloudberries are gathered in Karelia’s wetlands and delivered frozen to the factory. Petrovksy produces more berry-infused liqueurs too: rowanberry with cognac, cranberry with cognac, lingonberry with pepper… The latter, an unusual combination that works surprisingly well, is a personal favorite of the factory’s director: lingonberry mors, red pepper infused alcohol, and black pepper extract, adjusted to 38% alcohol.

I leave the Petrovsky Liquor Factory with new respect for the infamous balsam, a tipsy gait, and a bag full of bottles – you know, for research. Sadly, you’re unlikely to find Karelian balsam in stores outside of Russia. But there’s still a solution – make your own! Get your 10,000 liter tank ready and follow the recipe below.

Karelian balsam

Yields 10,000 liters

375 l “balsam” infused alcohol (1st run, see below)

100 l raspberry infused alcohol (1st and 2nd runs)

316 l cranberry infused alcohol (1st and 2nd runs)

220 l lingonberry infused alcohol (1st and 2nd runs)

58 l rowanberry infused alcohol (1st and 2nd runs)

64 l black rowanberry infused alcohol (1st and 2nd runs)

50 l bilberry infused alcohol (made with dried berries, 1st and 2nd runs)

150 l rowanberry infused alcohol (made with dried berries, 1st and 2nd runs)

50 kg honey

1.5 kg essential oil of balsam of Peru

0.5 kg lemon essential oil

1 kg rum essence

1 kg cherry essence

700 l sugar syrup (65.8% concentration)

300 l caramel color

1,000 l highly mineralized water (rich in iron, sulfate, and bicarbonate)

“high purity” rectified alcohol and filtered water, proportioned for 45% total alcohol content

“Balsam” infused alcohol

Yields 375 l liters

10 kg chaga mushroom

5 kg lingonberry leaves

5 kg bird cherry (fruits)

2 kg dog rose (hips)

1 kg juniper (berries)

2 kg small-leaved linden (fruits)

0.5 kg galangal (roots)

5 kg perforate St John’s-wort (flowers and leaves)

0.2 kg nutmeg (nuts)

0.5 kg oregano (tops of flowering stems)

0.5 kg yellow sweet clover (leaves and tops of flowering stems)

0.2 kg sage (leaves)

0.2 kg fir needles

0.2 kg plantain (leaves and tops of stems)

1 kg clover (flowers)

500 l mix of water and rectified alcohol with 50% alcohol content