Absinthe in Czech Republic, really? Yes! Unbeknownst to most, the country has a substantial and long-standing absinthe tradition. This shouldn’t be all that surprising, considering Central Europe’s taste for funky herbal liqueurs (recall, for example, Becherovka). There is evidence that absinthe was produced in Czech Republic as early as the second half of the 19th century, which is precisely when the drink’s popularity started growing throughout Europe. You can read absinthe’s tortured history elsewhere, but what interests us today is the emergence of Bohemian absinthes (Bohemian as in from Bohemia, the region that covers the western half of Czech Republic — nothing to do with gypsies or with would-be artists living in Williamsburg). According to the Absintherie, an absinthe shop cum bar cum museum in Prague:

Modern Bohemian-style absinthes are based on an old tradition of absinth substitute from the period of the First Republic (1918-1938). At that time in Prague, absinth was widely consumed especially in the Slavia Café, where a famous painting “Absinth drinker” by Viktor Oliva has been on display until today. Absinth was also popular in the Daliborka bar in Prague 6, where, among others, Czech poets Jiri Wolker and Vitezslav Nezval were often enjoying it.

Viktor Oliva – Absinthe Drinker

While the French and Swiss styles are produced by macerating herbs in alcohol, distilling, and often macerating again, Bohemian absinthe essentially stops after the first step. It should be noted, however, that the Czech did not hold the monopoly on imitation absinthe. Even in France, as quantity started replacing quality, one could buy cheap products that took all kinds of shortcuts (some deadly) in attempts to reproduce some of the attributes of the Green Fairy at a fraction of the cost — a fact that quite likely contributed to the drink’s eventual ban.

Fast-forward half a century, and the Velvet Revolution is eager to undo anything that the communists did, especially when it comes to banned stuff. Freedom is in the air, whether it’s of the speech, movement, or wormwood variety. At this point the rest of the world has mostly forgotten all about absinthe, but some Czech distillers are old enough to remember the times before the war. Times when they still ran their very own liquor businesses, before they became stigmatized as capitalist pariahs and had their properties confiscated for the benefit of The People. Times when they could make a pretty penny by cashing in on the nefarious appeal of the Green Fairy. These distillers set out to create a product that reflects their conflicted destiny: a First Republic absinthe substitute, produced following the very communist habit of making alcoholic beverages by mixing cheap neutral alcohol, flavors, and coloring. Prague becomes the paradise of the artificial bright green fairy with brands like Staroplzenecký and Hill’s. And despite the questionable production methods, these products should certainly be credited for the modern absinthe revival that would later follow.

In my misguided youth, I, too, discovered absinthe for all the wrong reasons. If you were a tourist in Prague in the early 00s, absinthe was everywhere in the streets. 70% alcohol, bright green, dirt cheap… What else could you possibly want? Before going clubbing in the old town, in a bathhouse converted into a four-story disco, I drank my shots of Staroplzenecký. Once back home, I inflicted upon my friends countless flaming absinthe concoctions that often sent them rushing for the kitchen sink. Around the same time, or maybe slightly later, I also began to educate myself on more respectable products, the revival stuff that doesn’t want to be seen anywhere near the Czech imposters. There are absinthes that can actually be enjoyed! And there are people going to great lengths to lift century-old bans and recreate the exact flavors of yesteryear. Still, back then, I was a dilettante pioneer in my neck of the woods: sale in the US remained prohibited, internet overseas shipping was expensive, products were obscure and sometimes overrated. Before long, I lost interest — my last bottles from that time would spend over a decade gathering dust.

And let’s face it: absinthe isn’t for everybody, especially absinthe made in the traditional French or Swiss styles, and especially for the American palate. If, like the vast majority of Americans, you tend not to like liquors with a heavy anise content that are typically drunk with water, such as ouzo or pastis, then you probably won’t like absinthe. If you do like anise, you might then prefer the convenience of choosing from a few well-established, readily available, and perfectly drinkable brands — Ricard, Pernod, Sans Rival Ouzo, or even Henri Bardouin for the purists — instead of discovering the wild world of absinthe with its dozens or even hundreds of names you’ve never heard of, often still requiring out-of-country purchases. And even if you like mysterious liquors acquired at great expense from, say, an online store in Germany, whose anise taste will numb your palate for the rest of the day, you may still not like the taste of absinthe. The maceration of a dozen varieties of herbs, many of which you’ve never consumed in any other context, creates flavors that can range from soapy to bitter (sometimes both), making absinthe very much an acquired taste.

And still, here I am, more than ten years after my original acquaintance with this beverage, writing a blog post titled “Absinthe, Part 1”. Under my Czech Impressions series, no less. So. What happened?

It all (re-)starts while I’m preparing for my trip to Central Europe back in early spring, looking for places to visit that could be blog-worthy. Sure, anything food- or beverage-related in Central Europe makes for good material, but what could be slightly off the beaten path? Then I remember the brightly-colored absinthes that still filled the store windows in Prague during my previous visit only a year or so before. Were they just the same as the ones that came on the market in the 1990s? Did they get better?

Way to go, Food Perestroika! In a country famous for its beers, a country that makes excellent fruit brandies, has a tradition of curative herbal liqueurs, and even produces some wines well worth trying, let’s blog about the trashiest beverage on the market! The one that locals barely ever drink; the one that’s gained an infamous reputation as tourist bait by being served with a freaking sugar cube set on fire! And where’s this stuff made, anyway? Aha! Now we’re onto something! Instead of organizing a green-vomit-laden bar crawl in the capital, let’s go where it all begins: the distillery. Who has ever visited an absinthe distillery? Not any typical Anglo-Saxon frat boy, I would think.

Still brainstorming, I have trouble forming a clear image in my mind of what an absinthe distillery looks like in Czech Republic. Will I discover people mixing third-grade products in their bathtubs? I begin to imagine a brand of absinthe made in a bathtub with beautiful and / or famous people bathing in it, with custom labels showing pictures of the people who bathed in each batch. Hmm… probably not. More realistically, it will be in some crumbling communist factory in a Prague suburb, run by the mafia, mixing third-grade products for sure, but in rusty tanks, under the drunken supervision of a ventripotent, probably balding interloper.

To shed light on this shady business, I start by tracking down the contact information for Hill’s absinthe (or absinth without an e, as this is how many of the Czech brands choose to spell the word). I immediately discover that there sure are a lot of websites for absinthes called Hill’s. There are two Czech sites with identical contents, hillsliquere.cz and hillsabsinth.cz, mentioning a distillery in Jindřichův Hradec and the distilling history of the Hill family. Then there’s a third site simply called absinth.cz. It tells the same family tales (this time in English), advertises the same standard Hill’s, plus a ton of other absinthes under the Hill’s and Euphoria brands, high-proof liquors in skull-shaped bottles, and various other pseudo-boundary-pushing products like Cocaine Vodka, Cannabis Beer, and Cannabis Lollipops. I cannot resist all this kitsch, and promptly compose an email politely asking for a visit to the distillery. No answer.

Never mind, it turns out there are even more Hill’s websites out there! The old-fashioned hillsabsinth.com seems to be the proud representative of Hill’s Liquere in North America (or more precisely, in Canada). Then there’s hills-absinthe.com, with a hyphen, an e at the end of absinth, a more contemporary site design, and a new bottle design that I haven’t seen on any other site. The owner is still Hill’s Liquere North America. I send another email, confident that somebody has to answer me sooner or later. And this time, the answer comes — straight from a member of the illustrious Hill family.

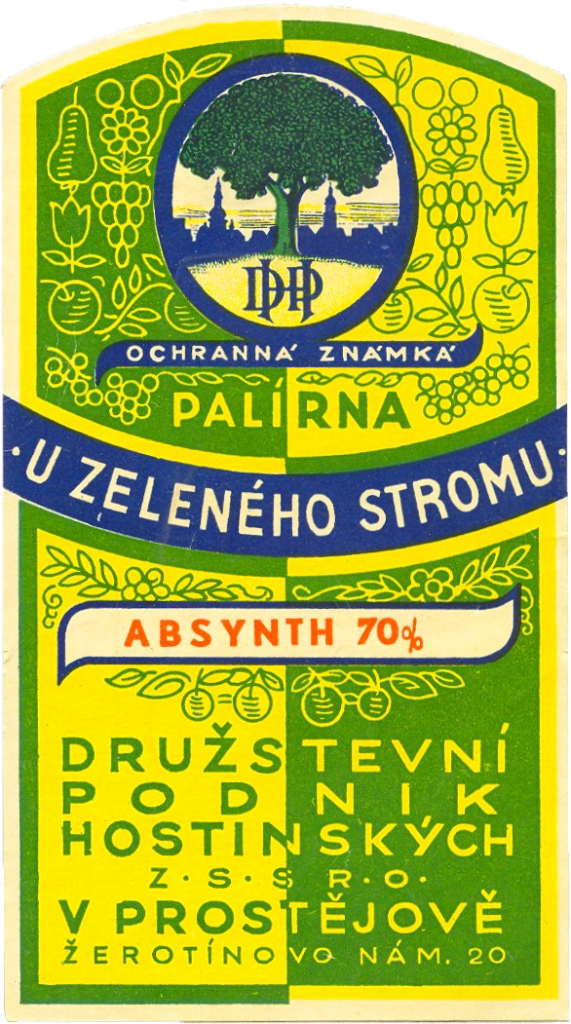

Dan Hill, apparently a distant relative of the late Radomil Hill (see here) and not a Canadian pop singer, no longer works with the Czech company Hill’s Liquere, but kept the name, and now has his abinsthe produced by a different distillery in Czech Republic. This other distillery is called u Zeleného Stromu (“by the Green Tree”). I guess this also explains the new web site and bottle design. With Dan’s invaluable help, I am able to arrange a tour of the distillery u Zeleného Stromu.

Somehow, it never occurs to me to try contacting L’Or Special Drinks, the maker of the Staroplzenecký absinthe of my misspent youth, which shares with Hill’s most of the Prague absinthe market (check out their product line here). One of the reasons is that, if at all possible, I want to compare products from a big company to those from a small family business (the bathtub, remember?). So to round out my research with something that would fit nicely in my travel itinerary, I decide to google “absinthe distillery moravia” (ironically, Moravia produces just as much “Bohemian” absinthe as Bohemia itself).

Once I scroll down past Google’s usual display of incompetence in the top results, I find a “family owned and operated fruit orchard [and] honey bee farm” that produces the usual range of traditional products, plus a handful of absinthes and other more unexpected beverages that I don’t really pay much attention to during my first cursory web browsing. “How perfect,” I say to myself, “a small slivovice maker who mixes some absinthe together on the side to supplement his income on the backs of those idiot tourists in the capital.” I send an email, and get an almost immediate answer inviting me to drop by any time.

At this point, I’m all set. I have appointments with both the large absinthe factory and the small family producer. Could be the mafia and the bathtub, but not together in the same place. Am I being eerily prescient, or completely naive? Let’s find out. Pack your suitcase, we’re going to Moravia — the other absinthe country!

Old Label from u Zeleného Stromu