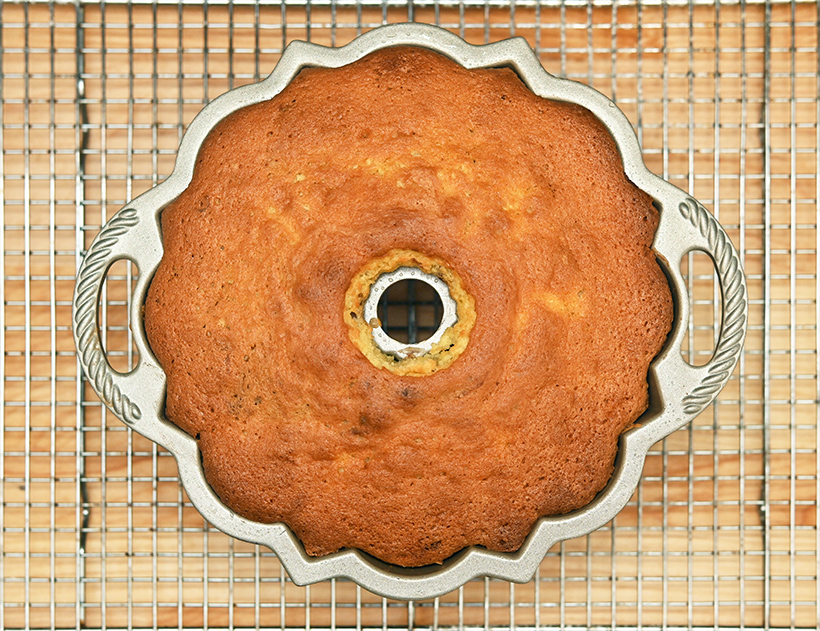

In Czech Republic, bábovka is a popular dessert. Unlike vánočka that’s made only for Christmas, it’s an everyday cake, easy and quick to prepare (one can even buy bábovka mix), perfect as a coffee cake or for the kids’ afternoon snack, and available in dozens of variations. Then why is it not more famous abroad, you may ask? Actually, it is, just under different names: Gugelhupf, kouglof, Bundt cake, and sometimes marble cake – these are all bábovkas!

Which version came first? Early Gugelhupf mentions are found in late-Medieval Austria, when it is served at major community events such as weddings and is decorated with flowers, candles, and seasonal fruits. The first known recipe is featured in Marx Rupolt‘s 1581 Ein new Kochbuch, a kind of textbook for professional chefs in training. In the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the name eventually comes to designate in Viennese cookbooks a rich cake flavored with rosewater and almond. Since there don’t seem to be such early mentions of bábovka anywhere, I’m gonna go out on a limb and say that the cake is imported into the Czech culinary repertoire by way of Vienna.

Gugelhupf later evolves to become a yeast dough cake with raisins and almonds baked in a special pan, the Gugelhupf mold (which seems to be brought to America by Jews in the early 20th century, eventually evolving into the Bundt mold that popularizes Bundt cake on this side of the pond). In Central Europe, Czechs, Slovaks, and Hungarians develop regional varieties, such as one filled with a layer of sweetened ground poppy seeds.

In the second half of the 19th century, baking powder is invented! People the world over decide they can’t be bothered to wait for yeast dough to rise anymore. As for those pesky poppy seeds that get stuck between your teeth, with the development of the Dutch process in the early 19th century, why not replace them with cocoa powder? Eventually, as long as it’s baked in the traditional mold, almost anything can be a Bundt cake, a bábovka, or even a Gugelhupf.

So here we are. Today, Czechs most often prepare bábovka as a marble cake, with one light layer flavored with vanilla, and a dark one mixed with cocoa powder. In some places, raisins, candied fruits, or chocolate chips are also common. But really, as long as you keep the Bundt mold, pretty much anything goes. Kynuta bábovka (leavened bábovka) is the original made with flour, eggs, milk, butter, and yeast. Trená bábovka (sponge bábovka) uses beaten egg whites and baking powder to give the cake volume and airiness. And check out this site (in Czech) for many more options: fast bábovka (with whole eggs), bábovka with whipped cream, bábovka with kefir, bábovka with oil; bábovka with zucchini, bacon and walnuts, apples, carrots, coconut, poppy seeds, or marzipan and nougat. With so much diversity, it’s tempting to just translate bábovka as cake! And if one needs any more proof of the degrading effect of the cupcake craze on mankind, there’s even a bábovka in a cup – a confection that has lost all of the attributes of the original…

I’m offering two recipes today: one marbled sponge bábovka, and one bábovka made with whipped cream, raisins, and Maraschino cherries. I did try a yeast dough bábovka as well, but to me the bready brioche-like taste and the airy but somewhat sticky texture that it produces felt less like the modern idea of a cake (although maybe some of this is due to the recipe I used).

These being simple desserts, I want to bake the best versions possible! Here are a few steps I’m taking towards that end:

- In the marbled bábovka, I’m using chocolate rather than cocoa powder because it imparts a richer chocolate taste (if you insist on using cocoa powder, you’ll need 15 g of it).

- In the fruit bábovka, the raisin-Maraschino cherry pairing is inspired by Genoa cake; it may not be typically Czech, but it’s delicious! Make sure to use real Maraschino cherries, like these or these. The whipped cream in the dough plays an essential role in preventing the fruits from sinking to the bottom while baking.

- Placing a baking dish of water on the bottom rack of your oven makes the bábovka dramatically moister!

- Why do people cook meat based on its internal temperature, but not cakes? Ovens often aren’t nearly as accurate in practice as their shiny digital displays claim, so baking times are only approximate. Just as with meat, an overcooked cake will be dry. So do yourself a favor and use a thermometer to test your cakes’ internal temperature.

- One more thing that recipes almost never do: I’ve adjusted the proportions exactly for a specific size of Bundt mold.

And then there’s the flour… Inevitably, when talking with Czechs about baking, the discussion will turn to Czech Republic’s unique categories of flour. When it comes to white flours in general, there are a few factors that vary: gluten content, wheat varieties, milling size, and freshness. I’ve talked about the latter here, basically stating the fresher, the better; don’t buy flour in bulk from the other end of the continent/world. In the US, flours are pretty much exclusively rated by gluten content: there’s bread flour with high gluten content, cake flour with low gluten, and all-purpose flour in between. The wheat varieties and milling sizes are rarely under your control: unless you mill your own, you get what you get. As far as I know, most countries in Europe use a similar system – except Italy (which has a gazillion different kinds) and Czech Republic. In the most common types of Czech flours, the gluten content and milling size come in preset combinations:

- T400 polohrubá (half-coarse) flour must pass through a 366 μm sieve (for at least 96% of its content).

- T450 hrubá (coarse) flour must pass through a 485 μm sieve (for at least 96% of its content).

- T530, hladká (smooth) flour must pass through a 257 μm sieve (for at least 96% of its content).

- T1000 chlebová (bread) flour must pass through a 257 μm sieve (for at least 96% of its content).

The T number is the ash (i.e., mineral) content, measured by burning the flour, and it’s proportional to the amount of gluten protein. In other words, hladká and chlebová flours are quite fine and have medium and high gluten contents, respectively, whereas polohrubá and hrubá are coarser and have low gluten contents. As a point of comparison, in the US, I think standards specify that 98 percent of the flour must pass through a 212 μm sieve.

So we have a rough equivalence between US and Czech flours. My dear Czech expats and fellow Czech culture lovers, print this and tape it to your kitchen cabinet: T1000 chlebová = bread flour, T530 hladká = AP flour, and T400 polohrubá = cake flour. T450 hrubá, commonly used for Czech dumplings, doesn’t have a good equivalent – farina, maybe?

Bábovka generally calls for polohrubá flour, and this gives people a chance to split hairs: “The milling size isn’t the same, the result is different!!!” There is some mathematical truth to this for sure, and coarser flour absorbs more water. But I still have several solid arguments against going out of your way to buy Czech flour:

- The entire world makes perfectly good cakes without Czech flour. I mean, can you even name a famous Czech baker?

- Yes, polohrubá flour absorbs more water than cake flour. If you must, simply reduce the amount of liquid in your Czech recipes when using cake flour. Done! And make sure that you’re using cake flour, not AP flour.

- Flour has a shelf life and storage requirements. Shipping it from Czech Republic in unknown conditions is likely to produce somewhat inferior results.

- Using exact proportions (instead of a cup of this and a tablespoon of that) and carefully following my instructions (that dish of water on the bottom rack; checking the cake’s internal temperature) are way more important than using Czech flour!

Marbled bábovka

Yields 1 cake

60 g 70% bitter chocolate, chopped

180 g cake flour

8 g baking powder

1.5 g salt

80 g milk

9 g vanilla extract

130 g (4-5) egg whites

105 g granulated sugar

180 g butter, medium dice, softened, plus some to grease the mold

120 g confectioners’ sugar (plus some for decoration)

70 g (4-5) egg yolks

- Place a baking dish of water on the bottom rack of the oven, and heat the oven to 175 C / 350 F.

- Melt the chocolate in the microwave for about 2 minutes, then stir and set aside.

- In a bowl, combine the cake flour, baking powder, and salt.

- In another container, mix the milk and vanilla extract.

- In the bowl of a stand mixer fitted with the whisk attachment, beat the egg whites to soft peaks, then slowly mix in the granulated sugar on low speed. Transfer to another bowl and reserve in the refrigerator.

- Fit the stand mixer with the paddle attachment, wipe the bowl with a paper towel, and beat the butter on medium-high speed for 1 minute. Slowly mix in the confectioners’ sugar on low speed, then beat to a light color on medium-high. Back on low speed, mix in the egg yolks one at a time, followed by half of the flour mixture, half of the vanilla milk, then the remaining flour mixture, then the remaining vanilla milk, waiting for each ingredient to be incorporated between each addition.

- Fold the egg whites into the mixture with a spatula. Transfer 1/3 of the resulting batter (about 275 g) to another bowl, and gently fold the melted chocolate into it.

- Grease a 1.5 liter (6 cup) Bundt pan generously with butter, making sure that you cover the entire inside of the mold. Spread half of the plain batter (about 275 g) into the pan, then all of the chocolate batter, then the remaining plain batter. There should be about 2 cm of empty space left in the mold. Run a knife through the batter in a zigzag pattern (this is what creates the marbling).

- Bake on the middle rack of the oven for about 50 minutes, to an internal temperature of 96 C / 205 F. About 15 minutes before the end, if the color starts to get too dark, cover with foil.

- Cool the pan on a wire rack for 10 minutes. If any part of the cake is sticking too far out of the mold, cut it off to make the cake flat, then invert onto a serving dish, removing the mold, and let cool completely.

- Sprinkle with confectioners’ sugar before serving, and cut into slices.

Cream bábovka with raisins and Maraschino cherries

Yields 1 cake

210 g heavy cream

140 g (about 3) eggs

140 g sugar

85 g almond flour

160 g cake flour

5 g baking powder

1 g salt

160 g jumbo raisins

30 g dark rum

30 g water

120 g drained Maraschino cherries

5 g butter

- Place a baking dish of water on the bottom rack of the oven, and heat the oven to 200 C / 400 F.

- In the bowl of an electric mixer fitted with the whisk attachment, whip the heavy cream to medium-firm peaks. Transfer to another bowl and reserve in the refrigerator.

- Fit the stand mixer with the paddle attachment, wipe the bowl with a paper towel, and beat the eggs on medium-high speed. Add the sugar and continue mixing for about 1 minute, to a pale ribbon. Switching to low speed, add in the almond flour, cake flour, baking powder, and salt, and mix just long enough to combine.

- Fold the whipped cream into the mixture with a spatula, and set aside.

- Combine the raisins, rum, and water in a bowl, and microwave for 1 minute. Let steep for 10 minutes. Drain.

- Halve the cherries, and mix with the drained raisins. Fold about 3/4 of the combined fruits into the batter.

- Grease a 1.5 liter (6 cup) Bundt pan generously with butter, making sure that you cover the entire inside of the mold. Evenly pour the batter, then shallowly press the remaining raisins and cherries into it.

- Bake on the middle rack of the oven for about 40 minutes, to an internal temperature of 96 C / 205 F. About 15 minutes before the end, if the color starts to get too dark, cover with foil.

- Cool the pan on a wire rack for 10 minutes. If any part of the cake is sticking too far out of the mold, cut it off to make the cake flat, then invert onto a serving dish, removing the mold, and let cool completely.

- Sprinkle with confectioners’ sugar before serving, and cut into slices.

2 comments

Maybe you could also write the recipe using teaspoons and cups instead of just grams. I am not sure how to convert.

Buy a scale, that’s the single most useful kitchen tool you can have.