Here’s a recipe that I wanted to give you before the holidays: a traditional Czech whole roast duck! Pečená kachna is a classic holiday dish in Czech Republic (you can also enjoy it year-round in many Prague restaurants, such as U Modré Kachničky), and the garnishes never change: cabbage (preferably red), potato dumplings (and/or bread dumplings), and, in the most luxurious recipes, stuffing made with meat, nuts, or fruits. Celebrity chef Andrew Zimmern remembers that once upon a time, Czech roast duck could be ordered in many restaurants in New York’s Yorkville neighborhood. Nowadays, Central European restaurants have all but disappeared from that little corner of the Upper East Side, with only German restaurant Heidelberg still offering Gebratene Ente, “succulent roast duckling, with a potato dumpling and red cabbage.”

Enter my very own version of pečená kachna, which is sort of traditional… except it’s not whole, it’s not entirely roasted, it only comes with some of the usual trimmings, and it involves some ingredients that many Czechs have never eaten. Let me explain.

First, I must admit that I stand defeated: I failed to create a whole roast duck that was good enough to be published on this blog. Sure, I could have created a recipe where the breast is tender and rosy and the legs are tough as shoe leather, or one where the leg meat falls off the bone and the breast looks like a dry brown blob, or something in the middle where neither the breast nor the legs really satisfy anyone. But, alas, you just can’t get both the legs and breast perfect together. Spatchcocking the bird doesn’t help, and, although I didn’t try, I doubt that a rotisserie would fare much better. This is simple math: the breast should be cooked to 54 C / 130 F, and the legs to 74 C / 165 F, but a traditional oven doesn’t let you reach those two different temperatures at the same time on a whole bird. It’s the same dilemma that we face when roasting a chicken or a turkey, but further exacerbated because the breast has to be served medium and not well done, and duck legs are quite tough. Then there’s the skin. The outside should be crispy, and the layer of fat underneath should be cooked enough that it’s tender, not rubbery. All that while the breast itself remains pink.

And yet, there’s one famous recipe for whole duck that yields pretty good results: the Peking duck. Peking duck, however, is cooked vertically in special ovens, and that’s not something you’re gonna replicate at home that easily. Besides, the birds are young and quite small, and the meat plays second fiddle to the crispy skin. Peking duck is delicious, but it vastly differs in concept from Czech roast duck.

If we look instead to the West, high-end restaurants avoid serving whole ducks. The breasts and legs are generally cooked separately; in French there’s a canned expression for this: canard en deux cuissons. Sometimes, the two cooking methods yield two separate dishes, so that a whole roast duck can perhaps be presented to the patrons, the breast served first, and the legs rushed to the kitchen to be recooked and served next – unless the cook uses the legs from another duck! Read Heston Blumenthal or Nathan Myhrvold and you won’t see a single recipe for a whole roast duck. So I can at least take consolation in the fact that even the greatest chefs haven’t yet cracked this nut.

I’ve had this recipe in preparation for several years now, partly because I don’t eat duck every day, but mainly because I’ve been trying and trying to perfect a whole roast duck. My decision to stop chasing this elusive ideal makes things considerably easier:

- I already have a couple of great recipes for duck or goose leg confit (here and here), so why not use one of them and just crisp the skin before serving? This is by far the best way to cook duck legs.

- I’m keeping the breast on the bone so I can still have a reasonably dramatic presentation reminiscent of a whole bird. To get the most tender meat and crispy skin, I’m taking inspiration from Alain Senderens’s Canard Apicius 2010, where the duck is “blanched” in stock for a few minutes then left to marinate for a couple of days, and then I apply a dry brine to the skin. If I had an infinite supply of time and ducks, I could probably fine-tune the process a bit, but rest assured this is already a damn fine roast duck breast!

You can’t really have a traditional Czech duck without knedlík, potato or bread dumpling. Actually, you can’t have any kind of Czech meal without knedlík. I’ve already published a recipe in my vepřo-knedlo-zelo post, but I’m modifying it here by using potato buns in place of white bread (thus making it both a potato and a bread dumpling at once), and leveraging my duck by-products (skin and fat) rather than using bacon and butter.

Tradition would also dictate finishing the dish with a side of cabbage (as in the vepřo-knedlo-zelo), but making (and eating) the same stuff over and over gets monotonous. Surely, Czech Republic grows more produce than just cabbage! So let’s try something different. Say… quince! I don’t remember how this idea first came to me, but quince, while not exactly popular, does make semi-regular appearances in the cuisines and liquor cabinets of Central Europe, as quince brandy, quince paste, or quince pie, to name a few. Because quinces aren’t as sweet as apples and can withstand long cooking times without falling apart, they’re also really good in savory dishes. Here, I’m making a stew similar to a vegetarian goulash.

I know it seems like a pretty involved recipe, but with a little bit of organization, it doesn’t take all that long. Just make sure you plan enough time to marinate and dry-brine the duck breast. You can prepare the quince stew and knedlík one or two days ahead, then on the day of your meal, you’re left with just roasting and putting it all together. I wrote that the recipe makes 4 servings, but you could easily feed 5 people without changing the proportions.

Duck fabrication

Yields 4 servings

1 whole duck, 2.5 to 3 kg

- Your typical whole duck will come with the neck and a bag containing the offals, tucked inside the cavity. Take them out and reserve.

- Cut off the remaining neck skin. This should be a long strip of skin hanging from the breast; if it’s not there, you can cut off some skin from the back of the carcass once you’ve separated the wings, legs, and breast (see below). Reserve for the knedlík.

- Using a knife, separate the wings at the shoulder joints, leaving as much meat as possible on the carcass. Reserve wings for the duck stock.

- Separate the whole legs at the hip joints, this time taking as much meat as possible. Reserve for the duck confit.

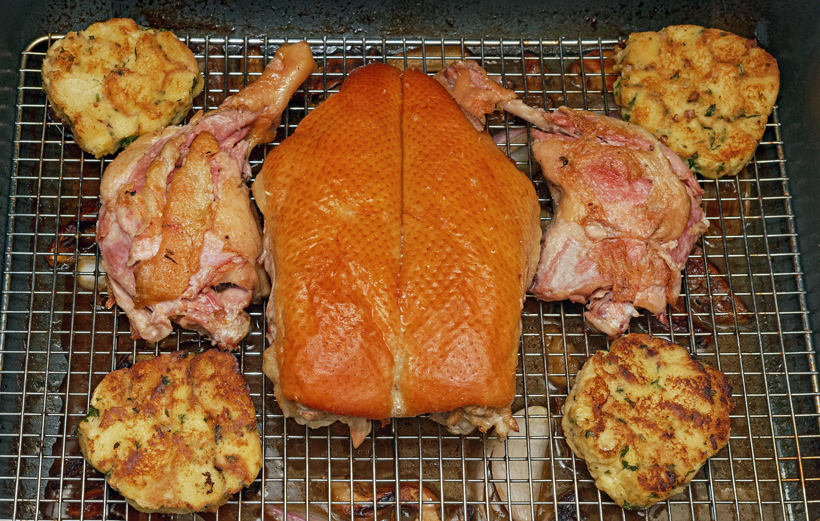

- Using poultry shears, cut through the carcass lengthwise in order to separate the breast (still on the bone). The legs and breast should look as follows:

- Chop the remaining carcass and neck in half using a cleaver. Cut the wings in half with a knife. Discard the offals (or, if you want to eat them, add them to the pan when roasting the duck breast, around midtime).

Duck stock

Yields 4 servings

duck bones (wings, neck, carcass)

15 g canola oil

250 g peeled onion, large dice

150 g peeled carrot, large dice

150 g celery, large dice

1 garlic clove

salt

2000 g water

2 thyme sprigs

- In the pot of a pressure cooker over high heat, sauté the duck bones in canola oil until brown on all sides. Add the onion, carrot, celery, and garlic. Season with salt, and stir for 2-3 minutes.

- Add the water and thyme. Cover, bring to pressure, then cook under pressure for 1 hour.

- Let cool for 30 minutes, then pass through a chinois, discarding the solids. Transfer to pint containers, and refrigerate for at least 12 hours.

- Once the stock is cold, remove and discard the congealed fat from the surface.

Duck confit

Yields 4 servings

2 (about 700 g) duck legs

sea salt (see below)

curing salt (see below)

1 garlic clove, peeled and smashed

4 thyme sprigs

2 peppercorns, crushed

1 clove

1 bay leaf

100 g duck fat

- Weigh the legs, then weigh 2% of that weight in sea salt and 0.1% in curing salt. In a small container, combine the sea salt, curing salt, garlic, thyme, peppercorns, clove, and bay leaf. Rub the seasoning all over the legs.

- Place the duck legs and duck fat into a sous-vide pouch. Cook in a 74 C / 165 F water bath for 20 hours.

- Take 50 g of duck fat out of the sous-vide pouch and reserve for the knedlík and roast duck breast. Reseal the pouch, and reserve.

Quince stew

Yields 4 servings

400 g (about 2) whole quinces

5 g lemon juice

10 g olive oil

10 g butter

85 g peeled onion, small dice

6 g peeled garlic cloves, minced

2 g smoked paprika

50 g red wine

70 g tomato purée

200 g chicken stock (plus some extra; see below)

0.3 g lemon zest, finely grated

6 g sugar

30 g heavy cream

- Peel and core the quinces, then cut each one into 6-8 segments, depending on their size. Reserve in a large bowl of cold water mixed with the lemon juice.

- Heat the olive oil and butter in a pot over medium heat. Add the onion and garlic, and sauté until golden brown. Stir in the paprika and cook for one more minute.

- Pour in the wine and reduce by approximately half. Add the tomato purée, quince, chicken stock, and lemon zest. Simmer without a lid for about 1 hour, stirring occasionally, until very tender.

- Transfer the quince to a bowl, and pour the sauce into a blender. Add the sugar and heavy cream to the sauce, and blend until smooth. You want the texture to be a thick sauce, not a purée. If needed, add a bit more chicken stock to thin it out. Rectify the salt seasoning.

- Pour the sauce over the quince, let cool, and refrigerate.

Potato bread knedlík

Yields about 4 slices

155 g potato buns with half of the crust removed

16 g duck skin, brunoise

25 g peeled shallot, brunoise

50 g egg

85 g milk

4.5 g parsley, finely chopped

salt

black pepper, ground

pinch nutmeg, ground

canola oil spray

- Cut the buns into 2 cm cubes. Transfer to a baking sheet, and toast in a 175 C / 350 F oven for about 15 minutes, until golden brown.

- In a saucepan over medium heat, sauté the duck skin until crispy, then add the shallot, and cook until golden brown. Let cool.

- In a bowl, combine the egg, milk, and parsley. Add the bread, duck skin, and shallot. Season with salt, pepper, and nutmeg, then mix well. Let rest for 30 minutes, stirring every 10 minutes or so.

- Spray a 30 cm x 30 cm piece of foil with canola oil. Pour the bread mixture onto the foil, and shape into an 8 cm long log (the diameter will be a bit less than 7 cm). Wrap and seal tightly by twisting the ends of the foil.

- Bring a pot of water to a boil. Immerse the foil-wrapped bread dumpling log, place a small lid on top to keep it submerged, and simmer gently for 20 minutes. Take out of the water, let cool, and refrigerate.

Roast duck breast

Yields 4 servings

duck stock

duck breast

salt (see below)

baking powder (see below)

120 g peeled shallots, quartered

175 g cleaned fresh porcini mushrooms, quartered

30 g duck fat, warm

salt

black pepper, ground

- Bring the duck stock to a boil in a large pot over high heat. Turn off the heat, then add the duck breast and let sit for 5 minutes.

- Remove the breast from the stock, then let the stock cool. Return the breast to the pot, cover and refrigerate for 2 days.

- Remove the breast from the stock (again). Pass the stock through a chinois, and return to the refrigerator.

- Pat dry the duck breast with paper towels. Measure 0.35% of the weight of the breast (still on the bone) in salt, and 0.05% in baking powder. Combine the salt and baking powder in a container, then rub onto the breast. Refrigerate, uncovered, for 12 hours.

- Take the duck breast out of the refrigerator, prick the skin all over with a fork, and let sit for a couple of hours, until close to room temperature.

- In a saucepan over high heat, reduce the duck stock to 600 g, then transfer to a large oven-proof dish (which you’ll also use to roast the duck breast).

- In a pan over high heat, sauté the shallots and porcini in 2/3 of the duck fat until golden brown. Season with salt and pepper, then transfer to the dish with the reduced stock.

- Rub the duck breast with the remaining warm duck fat, and place on a rack on top of the shallots, porcini, and stock. Roast in a 250 C / 500 F oven for 25-30 minutes, until the breast reaches an internal temperature of 52-54 C / 125-130 F near the bone. At midtime, add some water if most of the stock has evaporated.

- Take the dish out of the oven, and immediately proceed with assembly below.

Assembly

Yields 4 servings

duck confit

roast duck breast

quince stew

100 g cottage cheese

potato bread knedlík

20 g duck fat

- Reheat the duck confit in a 74 C / 165 F water bath for about 10 minutes. Open the sous-vide pouch, and place the duck legs on the rack next to the roast duck breast.

- Reheat the quince stew over low heat for about 10 minutes. Spoon dollops of cottage cheese on top before serving.

- Take the knedlík out of the foil, and cut into 4 even slices, discarding the butt ends.

- Turn on your oven’s broiler, and return the dish with the duck breast and legs to the oven. Broil until the skin turns a rich brown color. Make sure to check regularly; this goes fast! Take out of the oven and reserve.

- In a pan over medium heat, sauté the knedlík slices in the duck fat until lightly brown on both sides. Place the knedlík slices next to the roast duck breast, and bring the dish to your guests.

- Place the duck breast and legs on a carving board. Bone the breast, then slice each half. Bone the duck legs.

- On each plate, arrange the following in quadrants: one slice of knedlík topped with some duck confit, a few duck breast slices topped with some jus from the roast pan, some porcini and shallots, a portion of quince stew.