In my recent post about Murmansk, I talked a bit about the Sami people and the Kola Peninsula. Today, we’re heading to the very heart of the Peninsula, to the village of Lovozero, known as the Sami capital of Russia. But let me first digress about the history of the Sami…

The Sami belong to a group of Uralic peoples who started to move from their home Volga region (west of the Urals) around the middle of the second millennium BC. Using the ancient river routes of northern Russia, they settled in the regions between Karelia and the Finnish Lakeland. The group that settled in the latter region became the Sami, and later on it migrated further north to occupy the area along the coast of Finnmark, the inland of northern Fennoscandia, and the Kola Peninsula.

For centuries the Sami had relatively little contact with either the Scandinavians or the Russians. In the 14th century, the bubonic plague precipitated the economic division between the Sea Sámi who fished extensively off the coast, and the Mountain Sámi who hunted reindeer and small-game animals. While Norway’s population was decimated by the plague, the Sami were relatively spared thanks to their isolation. As a result, the local authorities offered incentives to the Sami to settle further south on the newly vacant farmlands along the fjords and inland waterways, where they pursued a combination of farming, cattle raising, trapping, and fishing. Meanwhile, the Mountain Sami, whose proportion gradually shrank to 10% of the total Sami population, continued to hunt wild reindeer. Around 1500, they started to tame these animals into herding groups and became the reindeer nomads often associated with the Sami lifestyle, following the annual reindeer migrations and criss-crossing the borders of Norway, Sweden, and Russia.

In the 19th century, Norway and Sweden started to more aggressively assert sovereignty in the north, and targeted the Sami with policies aimed at assimilation. During late 19th and first half of 20th centuries, the Sami language and way of life came increasingly under pressure from forced cultural normalization.

The situation in the Kola Peninsula was similar. From 1928, the Sami (like the rest of Russia’s agricultural sector) were subject to collectivization, first in small collective farms, then in larger consolidated state farms. Like the majority of the Russian population, they were also victims of purges and repression, and they were sent to the gulags. Traditional herding practices were replaced with permanent settlements, which resulted in the Sami gradually losing their language and their culture. They were progressively forced to settle in the village of Lovozero, where one of the reindeer farms was located. The Peninsula was also drastically industrialized and militarized. Between 1925 and 1935, significant deposits of apatite, sulfide, iron, and titanium were discovered there. Some territories were flooded to construct hydroelectric plants. Secret military installations were built, in particular related to naval production.

By the end of the 20th century, Russia counted approximately 2,000 Sami (versus 40,000 in Norway, 20,000 in Sweden, and 7,000 in Finland). The USSR collapsed, but the Sami have inherited its cultural and ecological threats. Regulations and industrialization have made access to some sacred sites more difficult. Vast areas have been destroyed by mining. Radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel from the Chernobyl catastrophe have been stored in the waters off the Kola Peninsula. And the recent oil and natural gas exploration in the Barents Sea poses new risks to the environment.

Though some continue to herd reindeer across much of the region, about half of the Russian Sami live in urbanized areas, mainly in Lovozero. Lovozero, population 3000, was founded in 1574 as the settlement of Loyyavrsiyt (literally “settlement of strong people by the lake” in Sami). Besides the agricultural and reindeer husbandry cooperative, Tundra, the main economic activities in the village are fishing, hunting, and picking cloudberries.

But what brings me to the area isn’t an ethnographic expedition on Sami culture. I’m actually here with a few friends for a snowmobile tour on Lake Lovozero. One might point out that there’s a contradiction between my lengthy account of the threats that endanger the Sami people and my frivolous little touristic trip on a form of transportation that’s not known as the most eco-friendly. But Lovozero is not the Adirondacks and you don’t see groups of drunks racing across the lake for fun – in the area, outside of the village, snowmobiles are the only practical form of transportation, and Sami use them too. Would I be better off heading to a Sami themepark to watch locals wearing costumes perform dances three times a day for busloads of tourists? Probably not, so I opted for something closer to my idea of a good trip: a tour with no tourists but us.

Getting to Lovozero takes some time. Your best shot is probably to fly to Murmansk and arrange for a car to pick you up for the 2 1/2 hour drive to the village. Should you decide, like us, to visit Karelia first, you can board an overnight train in Petrozavodsk and arrive in Olenegorsk (a small town known for its iron mines) 16 hours later, whence you can be driven to Lovozero in a bit over an hour.

Lovozero might be the end of the road, but it’s not the end of the journey. From here, we transfer our luggage to a sled, gear up, and hop onto snowmobiles. The camp where we’re staying, called Bear’s Corner, is located on the other side of the lake, another hour away.

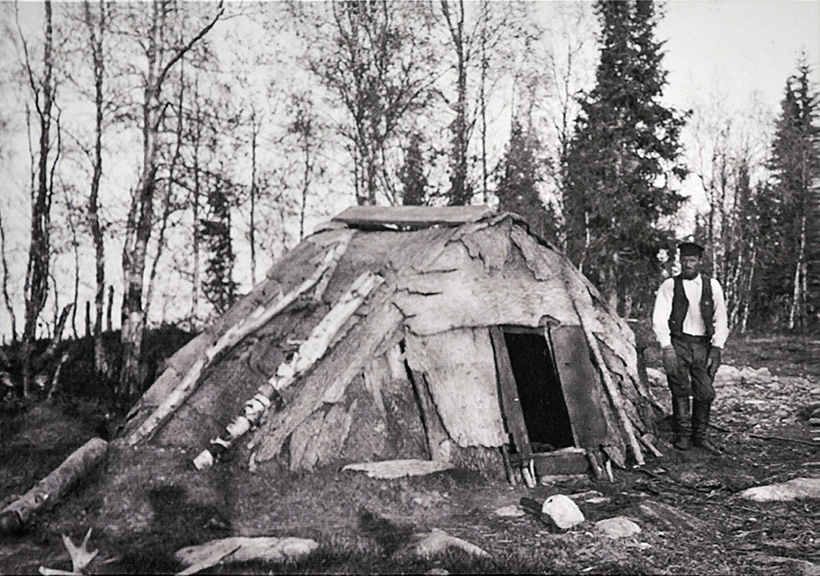

On this remote part of the lake, the camp owners Viktor and Anna have built a small survivalist village. There are several individual traditional dwellings for guests (named chum or vyezha depending on their shape), each heated by a wood-fired stove that someone will come feed for you regularly. A more modern-looking house is occupied by the staff and includes one or two extra guest rooms. There’s an outhouse and an authentic Russian banya – wood fired, burning hot – where you can lash yourself with birch branches after throwing some water on the stones, then pour a bucket of ice cold water over your head or just go outside to roll yourself in the snow. In the middle of the complex, a large chum hosts the dining/living room and the kitchen (I’ll dedicate a separate post to this). Solar panels provide (some) electricity to the common parts, and if you walk around the camp waving your phone like an idiot, you might even catch a faint signal. After a whole day outside, an hour in the banya, and a copious dinner, you’ll sleep like a log. I hear there were magnificent northern lights the first night of our trip, but despite attempts to wake me up, I just slept through it all!

It’s true that we had a pretty busy schedule for the day of our arrival: right after the lengthy trip and a sizeable lunch, we were headed to visit a reindeer herder, then off for some ice fishing before sunset.

The reindeer herder’s whole operation must be pretty small, as I don’t remember seeing more than a handful of animals. But they serve a very real purpose: together with the fish that can be caught in the lake, they constitute the bulk of the food eaten at the camp! Viktor has brought the reindeer some snacks, but the rest of the time, they dig in the snow to find reindeer moss, a very cold-hardy species of lichen.

Next stop: ice fishing. Why is it that guides always insist on showing you how to do things the hard way? We could have drilled a dozen holes in a couple minutes with an electric or gas-powered auger, but no… Instead, we’re spending half an hour messing about with a hand auger, in the name of tradition. Which in turn leaves less time for fishing, let alone drilling more holes. Good thing we’re not counting on our catch to make dinner that evening, as we get a single yellow perch. We let it go, and head back to the camp.

The next day, we’re heading to nearby Lake Seydozero (Seydyavr in Sami), which is part of a nature reserve protected by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Ecology of the Region of Murmansk. We make a few stops on the way, to check out some natural curiosities and to light a fire so we can warm up and have a bite.

A small reservoir sandwiched among the Lovozero Tundra mountains, Seydozero is a sacred lake for the Sami (seyd and yavr mean, respectively, “sacred object” and “lake” in Sami, while ozero means “lake” in Russian). The surrounding mountains create their own microclimate. The nature reserve was created in 1982 with the objectives of preserving the rare species of animals, birds, and plants it contains, and protecting the traditional habitat and cultural objects of the local Sami. It was more or less abandoned in the nineties, until the Murmansk region reorganized it in 2002.

On the northern shore of the lake, one of the steep cliffs features the 70-meter tall and 30-meter wide silhouette of Kuiva the Giant. Traditional Sami religion is closely connected to the land and the supernatural. It reveres natural sacred sites like mountains, springs, or land formations, and man-made ones such as petroglyphs and labyrinths. The legend of Kuiva was first recorded by the Swedish ethnographer Gustav Hallström in 1910. It goes something like this…

In ancient times, the ancestors of the Sami came to the valley of the Lovozero Tundra mountains and met the evil giant Kuiva, who attacked them. After a big battle (big by Sami standards, at least), Kuiva prevailed and killed many of his opponents – red eudialyte stones in the surrounding mountains symbolize the blood spilled that day. What were the survivors to do? Continue fighting, flee, come back with more men or a better plan? No, they’d call on their gods, of course! Said Sami gods weren’t too happy about the massacre, so they struck Kuiva with lightning. The giant turned into a rock and became a seyd, a sacred object, on the cliff that now bears its name. In different versions of the legend, Kuiva takes various forms, sometimes has accomplices, and commits various crimes against the good Sami people. The unusual sight continues to be an object of mythmaking in modern times and even feeds crackpot theories about the ancient Hyperborean civilization.

Recent studies have shown that the dark shape is formed by algae and microscopic fungi. It stands out most clearly in summer in cloudy weather, while in winter it’s much less contrasted and you can see the small rock shelves that compose the figure. Despite its constant exposure to the elements, the general silhouette of Kuiva hasn’t changed for more than 100 years.

On the way back from Seydozero, we get stopped at the entrance of the nature reserve. All of a sudden, two wardens who appeared out of nowhere decided to do the job they’re presumably paid for, with redoubled zeal to make up for their earlier absence. While visiting and camping (as well as foraging and amateur fishing) are allowed on the territory of the reserve, motor vehicles are not (you can read the official regulations in Russian here). One might wonder, then, why several travel agencies offer snowmobile tours of Seydozero. Or why visitors aren’t controlled before entering the reserve, at the designated entry point, which we used. Or why in my picture above there’s another snowmobile on the lake that clearly doesn’t belong to the wardens. But you see, this being Russia, there are always ways to obtain “special authorizations”…

Our guide Viktor explains to the wardens (with whom he is certainly already familiar) that he has such a special authorization, has had one for decades, just not on him; the wardens explain that last year’s authorizations are no longer valid this year. The wardens film our snowmobiles on their cell phones; our guide films the wardens filming the snowmobiles; the wardens film our guide filming them filming the snowmobiles. Viktor, who speaks only Russian, explains that none of us speaks Russian and we just understand each other implicitly; Viktor asks us in Russian to confirm that we don’t speak Russian and we shake our heads vigorously. The chief officer, who seems to have something to prove while his deputy does the best he can to stay out of the whole thing, waves his badge in front of our noses and keeps repeating in Russian his name and that we’re under arrest; we keep repeating in English that we don’t understand Russian. Having taken Viktor inside the wardens’ cabin, the chief writes several pages of reports while the argument continues, and Viktor explains that we have to leave urgently to catch a plane. The chief tries to call the Lovozero police but the connection is too poor to hear anything.

After a couple hours talking in circles while the rest of us freeze outside, Viktor bursts out of the wardens’ cabin and tells us to quickly hop on our snowmobiles and follow him without asking questions – we’ll be going straight back to the camp. You guessed it: we’re about to start a snowmobile chase with Russian law enforcement on Lake Lovozero. Inevitably, the two officers, even sharing the same rig, catch up with us. However, they obviously weren’t reckoning with our guide’s astuteness. I can’t hear what is said, but based on what happens next, I’m piecing events together as follows… Viktor convinces them to drive to the camp and sort everything out there, and points them in some direction towards the right. After they leave, he takes us through a kind of shortcut straight ahead between some trees, and we arrive at the camp just in front of the cops. As soon as we’re in, he bars the road: sorry guys, this is a private property! And as we guests are set to leave the next day before sunrise, we never see them again…

Surely it would be less douchey to control visitors on the way in, rather than try to fine them on the way back, let alone place them under arrest. But these are Russian cops for you. If you happen to visit Lake Seydozero and you see my hand-drawn mugshot on a wanted poster pinned to the wall of some wooden cabin, you’ll know why. Send me a picture, please.