Since you may not be able to travel to Croatia this summer, I’ve decided to bring Croatia to you. My last trip to the Dalmatian coast was already a few summers ago, so it’s about time I start writing about it! Let’s get started with… the Maraska distillery.

Some of my longtime readers might remember this recipe for maraschino cherries. In the post, I mention that Maraschino, unbeknownst to most people, wasn’t invented in Italy but in Croatia. Ten years later, I finally get to talk about the place where it all began: the town of Zadar (called Zara in Italian), in Dalmatia.

As per the Maraska company history and what I was told during my visit, the Marasca cherry tree, a cousin of the sour Morello cherry tree, was brought from Asia Minor to the Mediterranean during the Roman Empire. The sunny climate and rocky soils of northern Dalmatia and the Zadar hinterland turned out to be the perfect conditions to produce the best fruits, and the tree eventually became an autochthonous plant also known as maraška. The Dalmatia region’s oldest written document, dating from the 14th century and held at the State Archives in Zadar, mentions “one large Marasca cherry tree in the immediate vicinity of the city of Zadar, in the locality of Kolovare, in a vineyard by the Fountain, near the sea.”

Tradition holds that the first recipe for a liqueur made with Marasca cherries dates from the 16th century. The spirit, called ros solis, is produced by Dominican monks and used mainly as a medicine.

Maraschino, as it would become known, is believed to have been invented in Zadar in 1730 by botanist/pharmacist Bartolomeo Ferrari. It’s then further perfected by an Dalmatian-Italian café owner named Giuseppe Carceniga, who turns the hitherto medicinal product into a sipping liqueur. This coincides with a boom in alcohol production in Zadar, and by the late 18th century the city is home to a dozen distilleries making over 35 liqueurs, the most famous of which is Maraschino. The buzz attracts a young merchant named Francesco Drioli, who moves from Istria to Zadar and starts making Maraschino in a more industrial way, in 1768. Using modern equipment, he improves the distillation process to increase productivity, purity, and flavor all at once. Fabbrica Maraschino Francesco Drioli soon becomes the most important distillery in town, and its products make their way to the dinner tables of royal families all over Europe.

Drioli is also credited with introducing the woven straw bottle sleeve. The early 19th century is marked by great instability, and in 1806, Zadar is given to the short-lived Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy. The ongoing conflicts force Drioli to export his maraschino by land rather than by sea, but because of the harsh mountain roads that one must take to leave Dalmatia, all the bottles tend to arrive broken. The new hand-woven bottle sleeve prevents damage during transportation and its use to this day (at least on some of the bottles) contributes to the unique visual identity of Maraschino liqueur. Francesco Drioli dies shortly after this innovation, in 1808, but the distillery remains in the family. His nephew Giuseppe Salghetti-Drioli becomes the company’s first president, and is also instrumental in founding a glass factory in Zadar. Rather than importing bottles and sleeves, he brings the workers themselves over from Murano.

Liqueur production continues to improve and increase throughout the 19th century. The number of employees in the local factories rises sharply, reaching for example 500 to 600 workers during high season at the Drioli factory. As the reputation of Maraschino (and other liqueurs from Zadar) grows, new distilleries are established. In 1821, Girolamo Luxardo founds the Fabbrica di Maraschino Luxardo, which quickly acquires a good reputation. In 1861, Romano Vlahov opens a factory that produces Maraschino and also produces a well-known bitter aperitif named after himself, Vlahovac. Together, the Drioli-Luxardo-Vlahov triumvirate forms the Industria del Maraschino di Zara, though several other small factories also sell cherry brandy liqueurs.

In the late 19th century, the Zadar distilleries export over 400,000 bottles, of which as many as two-thirds are Maraschino (in less than two decades the export of Maraschino Zadar almost doubled). They’re considered among the most prestigious liqueur producers in the world, and Zadar is the world’s liqueur capital. The British court is particularly fond of Maraschino: in 1871 Queen Victoria orders the withdrawal of all warship from the Mediterranean just to ensure the safe passage of a Drioli shipment, and awards a certificate to Drioli to be a direct supplier without any intermediaries. In 1887, several dukes, including the Duke of York (later King George V) and the Duke of Edinburgh, visit the factory, allegedly calling Maraschino “the king of liqueurs” and strengthening its popularity back home. For its fateful maiden journey in 1912, the Titanic is stocked with Maraschino.

But WWII marks an ill turn of fate for the distilleries. In 1943 and 1944, Allied bombing destroys approximately 80% of buildings in Zadar. Most of the liqueur factories are destroyed, and production practically grinds to a halt. After Tito seizes the city in 1944, Zadar’s Italians are forced to flee in what might be called, depending on which view one takes, either persecution (many ethnic Italians were killed or just plain executed during the next few years), or mere swing of the pendulum (Italy had occupied Dalmatia for centuries; many rightly objected to Mussolini’s assertion that there was a “natural law” for stronger peoples to subject and dominate “inferior” peoples such as the “barbaric” Slavic peoples of Yugoslavia).

In the immediate post-war period, the living erstwhile owners of the three most important distilleries, Vittorio Salghetti-Drioli, Giorgio Luxardo, and Romano Vlahov, seek refuge in Italy and rebuild their businesses in Mira (near Venice), Torreglia (near Padua), and Bologna, respectively. They recapture some of their traditional markets, particularly the U.K., but Vlahov ultimately closes its doors in the 1970s, with Drioli following in the 1980s. Today, Luxardo is the last exile still standing (and, according to this article, uses a different strain of Marasca cherry).

Meanwhile, in Yugoslavia, the new communist government decides to rebuild one factory. All assets from the old operations, including some equipment and machinery that hasn’t been destroyed in the war, are confiscated by the state, and in 1946 the former liqueur heavyweights are consolidated into a single state enterprise called Maraska. The old Luxardo building, almost totally ruined by the Allied bombs, is rebuilt exactly as it was before and becomes the new company’s plant. Soon, the Yugoslavs are producing and selling their own version of Maraschino liqueur, using Francesco Drioli’s original recipe.

As is common in Eastern Europe, the communist period isn’t discussed much in Maraska’s marketing material. In any case, the company seems to emerge from the collapse of Yugoslavia alive and well. In 1993, it is transformed into a joint-stock venture.

Fast-forward to 2006… The iconic building on the embankment of the Adriatic has become less than ideal. The equipment is aging. The trucks delivering the raw materials or taking away the finished products get stuck in the traffic jams that plague the city center during the tourist season. Maraska sells the place (which will remain empty for many years and is now rumored to become a luxury hotel) and moves to a new location near the highway, leaving behind most of the old machinery and installing a brand new production line. Today, Maraska has about 150 employees split between sales, production, and other departments. It’s also part of the Mepas group, a big company in Croatia that owns various brands of snacks, sweets, detergent, and cosmetics, as well as shopping malls.

Maraska’s current product range, which fills a forty-page catalog, boggles the mind. The company is the number two producer of alcoholic beverages (behind Badel), number two producer of juices (behind Juicy), and number one producer of syrups in Croatia.

If Maraschino’s still the flagship alcoholic beverage, its heyday is behind it. It’s not consumed domestically that often anymore; it’s mostly sold to restaurants, hotels, and stores in Zadar. It has become a souvenir drink favored by tourists and reserved for export. The cherry brandy liqueur (essentially alcohol mixed with cherry juice, produced since the 19th century) is heading the same way: even if nearly every Croatian household has a bottle of it in their bar, they only drink it occasionally, and wouldn’t think of ordering it when they go out. It’s only popular with tourists and old-timers.

But some of the other traditional products are faring much better. Pelinkovac, a very bitter herbal liqueur, is the company’s best-selling product (at least it was in 2017). It’s made with seven herbs, including a prominent proportion of wormwood (pelin means wormwood in Croatia), followed by fennel, sage, and mint. Perhaps because it was invented by an ethnic Croat (Franjo Pokorny, who founded Badel in 1862) rather than by an ethnic Italian, it’s considered Croatia’s national drink. It’s also the top-selling alcoholic beverage at Badel. Being made in Zagreb, Badel’s Pelinkovac tops the sales in Central Croatia and Slavonia, whereas in Dalmatia it’s Maraska’s version – just a matter of local pride. Pelinkovac is consumed chilled with a slice of lemon, or with lemon juice, or, for those who really like sugar and bitterness, mixed with tonic (the Croatian version of the BeTon cocktail).

Orahovac, a green walnut liqueur (orah means walnut in Croatian), is number three on Maraska’s sales chart. It too follows a recipe over 150 years old, and it’s similar to Italian nocino.

So what’s number two in sales? Vodka, of course! Who needs tradition when one can just mix grain alcohol with tap water?! Like in Russia, Maraska doesn’t distill grain alcohol themselves, they buy it. With around 800,000 liters sold per year (still in 2017) Maraska’s Cosmopolitan vodka is also the second best-selling vodka on the Croatian market behind Badel’s Vigor vodka. Sales grow every year, and Maraska wants to be number one! “Our vodka is pure grain, distilled 7 times,” sings my host from the marketing department. It’s also offered in several flavors: raspberry, peach, mint, mojito, and strong (with an extra dose of grain alcohol for an inimitable bouquet). No cherry. The flavored vodkas are made with natural aromas (for the fruits, typically esters made from condensing the volatiles during the concentration process of juice), so they still have a connection with the fruit or plant with which they’re scented (except for mojito, duh). They tend to sell in very small amounts, their main purpose being to occupy more shelf space with the brand, thereby helping to sell more of the main, unflavored product.

Then it’s the other liqueurs. Maraska has a whole line of natural liquors: honey (called Medica; med means honey in Croatian), pear (Kruškovac, also a traditional product), blueberry (Borovnichka), cherry (Višnjevac, made with alcohol and pressed cherries rather than cherry juice), fig, lemon, and mandarin. And another line of “cocktail” liqueurs, made with aromas. Oh and there’s also Cherrica, similar to cherry brandy liqueur but with more cherry juice. And Vlahovac, old man Vlahov’s original bitter aperitif. And Amaro Zara, another bitter herbal liqueur. Several of the liqueurs are quite popular with younger customers as shots consumed in bars with a beer, supposedly with men choosing the bitter ones (there’s a reason Pelinkovac is number one), and women preferring the fruity flavors.

There’s rakija, too. And Slivovica, plum brandy, which also counts among the national drinks, though Maraska doesn’t sell a lot of it domestically because nearly everyone in Slavonia makes their own at home! As a result, anyone in Croatia with a Slavonian connection buys the homemade stuff, and only tourists and the occasional Dalmatian or Istrian buy industrial slivovica. The rest is exported to the German and US markets. In addition to slivovica, Maraska makes a Bartlett pear brandy, a grape pomace brandy (komovica), and a grape pomace brandy macerated with Dalmatian herbs (travarica).

And that’s not all! There are also two rums! And two gins! And a more cognac-like grape brandy! If there isn’t a drink for you in there, then you must love only tequila…

As for the non-alcoholic beverages, Maraska makes all kinds of juices and syrups. This a relatively new activity, but with over a dozen flavors across in multiple products and brands, it represents a substantial part of their business. Of course, this includes Marasca cherry juice and syrup.

So where does the company get all the fruits for their products, you may ask? As far as Marasca cherries are concerned, Maraska now owns a large orchard of over 200 hectares in the village of Zemunik Donji, near the Zadar airport. Approximately one hundred thousand trees yield an average of a thousand tons of cherries per year. This orchard was planted about 15 years ago on a former minefield. Before that, Maraska bought their cherries from small domestic producers, of which there are many in nearby villages. If you look at the picture of the orchard (courtesy of Maraska) at the top of this post you can clearly see the rocky soil. Many claim that the minerals from the rocks get into the cherries and that this, in combination with an abundance of sun that concentrates the flavors, explains the inimitable flavor of the Zadar Marasca cherry. (And supposedly, now that Maraska doesn’t buy from small local cherry producers anymore, Luxardo does!)

The other fruits are bought mostly in Croatia, or in neighboring markets when the domestic production isn’t enough. Whenever possible, that is. Certainly the Balkans don’t grow pineapples, and Central Europe even less so…

At the time of my visit, workers are busy picking the Marasca cherries. Some of them will be used for juice, others for syrup, and others for Maraschino and the various cherry liqueurs. The Maraska headquarters consists of two main buildings: one for the production of non-alcoholic beverages, and the other larger one for the production of alcoholic beverages and for offices. Plus a big tank filled with grain alcohol and connected to the plant via underground pipes. Storage is fairly limited, and the company tries to bottle/package according to forecasted demand and then sell quickly. Since I didn’t come all the way to Croatia to look at Tetra Pak filling machines, after putting on my paper suit and signing various forms I’m heading straight for the place where the booze is born.

Bad news: no pictures allowed inside. If it’s any consolation, the plant is nothing like a Scottish distillery where large copper stills stand in the middle of the room like shrines to immemorial tradition. A lot of the production doesn’t involve distillation (distillation doesn’t go on year-round; it wasn’t happening during my visit), but rather maceration and blending, and this is reflected in the overall layout of the unassuming industrial building.

The first room we visit is where the most involved steps of the production are conducted: the “raw materials” (cherries, plums, walnuts, herbs, etc.) are received, crushed (if needed), and taken to tanks for fermentation and maceration in grain alcohol. After a certain number of days, the macerate may be distilled – I see some steel tanks, a couple of small copper pot stills and a copper column still in a corner of the room. Considering the number of recipes Maraska has to juggle, there is no single path: some products require fermentation and some don’t, some call for full distillation only and some demand mixing distillates and macerates, others might skip this room altogether because they’re just an assembly of grain alcohol and juice.

The resulting distillates, some of the macerates, the grain alcohol, and the juices are all piped into the next room, where the “semi-finished products” are stored in tanks. Some distillates are stabilized in refrigerated tanks. Other tanks are used for blending, and others yet for storage. Finally, the blends are adjusted to achieve the desired levels of alcohol and sugar, filtered, sent to the company’s lab for analysis, and sent to the bottling line – the third room of the plant.

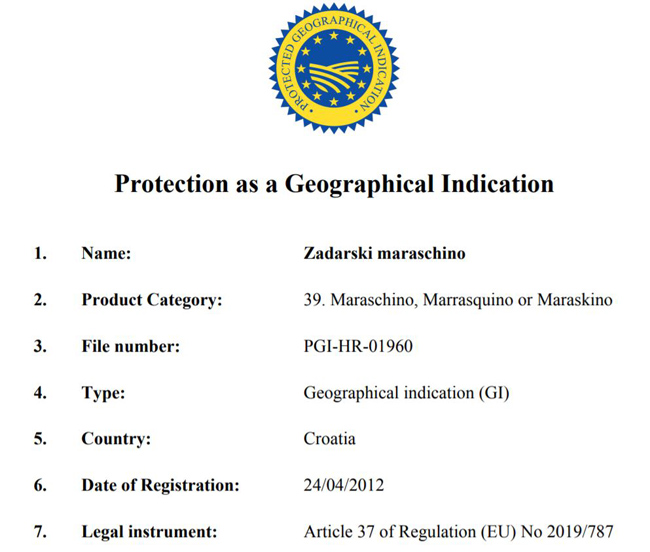

Let’s take Maraschino for instance. Zadar Maraschino benefits from a European Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), which requires producing within the three Dalmatian counties that stretch roughly from Zadar to Makarska, and following a specific production process. The fruits are fermented, macerated in grain alcohol, and distilled in the first room. In parallel, the stems and leaves are macerated and distilled, producing a more bitter and sour spirit. At first, both distillates are poured into separate tanks in the second room. Next, the distillates are blended and remain in storage tanks first to rest (the alcohol content at this stage is around 61-64%), then to wait until demand requires bottling a new batch (e.g., there’s not much demand for souvenir bottles outside of the tourist season). The Maraschino is made once a year, beginning right after the harvest, and the whole process takes about 6 months (including resting time), so the distillate blend waits for additional demand, then the remaining ingredients (such as sugar) are added, and the finished Maraschino heads for bottling. The Maraschino that hits the shelves, then, is between half a year and a year and a half old.

Slivovica takes less time to make, which makes sense since the recipe is much simpler (ferment, distill, rest). Same for cherry brandy liqueur, which merely requires blending juice and alcohol (blend, rest), and that’s called “alcoholized cherry juice” in Croatia. Vodka is even simpler, and it’s produced year-round.

“And that’s all we can say about this,” my hosts tell me. “There are secrets.” Indeed, they’ve been very protective of their fabrication details. How long does the maceration last? What are the other ingredients in Maraschino? In what proportion? What about the herbs in Pelinkovac, the herbal liqueur? Mum’s the word.

But in reality, there are fewer secrets than my hosts claim. To obtain a Protected Geographical Indication for Zadarski Maraschino, the Croatian Ministry of Agriculture had to describe not only the geographical area of production and the specificity of the final product, but also the method of production. And the application is available online here. This may not provide the entirety of Maraska’s treasured recipe, but it gives us plenty of details – and considering that Maraska is the only large producer of Zadar Maraschino, chances are they played a significant role in drafting this application!

The document covers a lot of topics that’s I’ve already mentioned (the history, the role of the Zadar region in growing Marasca cherries, highlights of the production), but also gives more explanations on how Maraschino is made:

- A fruit distillate is produced by stemming, crushing, and pitting the harvested cherries, fermenting them, adding ethanol of agricultural origin for maceration, then distilling the macerate in a copper pot still so that the resulting distillate contains 55-65% alcohol.

- A leaf distillate is produced by chopping cherry leaves (the main ingredient), stems, and bark, macerating them in an alcoholic solution for up to 60 days, then distilling the macerate in a copper pot still so that the resulting distillate contains 55-65% alcohol.

- Both distillates are blended together with ethanol of agricultural origin, with the constraint that the distillates must represent at least 33% of the total amount of alcohol by volume.

- Then sugar and water are added. There must be 300 to 360 g of sugar per liter, and the final alcohol content must reach a minimum of 32%.

The main surprise in this description is that Maraschino isn’t just the product of the distillation of cherries, like I was left to assume so far – it can also contain a hefty amount of grain alcohol! And in some circles, grain alcohol is a bad word (it’s the difference between a Johnnie Walker and a Talisker, for example).

So how do these revelations impact the taste of Maraschino? Is Maraska’s Zadar Maraschino the indisputable king of liqueurs? Or does exiled Luxardo steal the crown? And what about small producers? You’ll find out in my next post!