If I asked you where Europe’s largest vineyard is located, what would you say? Champagne, where world-renowned houses produce astronomical amounts of bubbly to quench the thirst of an ever-growing market? No – the large brands purchase their grapes from a multitude of small, local producers. Italy, perhaps, on the property of some homeland version of Gallo? Nope, not there either. Spain, then, because someone’s gotta make the juice that goes into all that sangria? Try again. The largest contiguous vineyard grown by a single winery is in Montenegro!

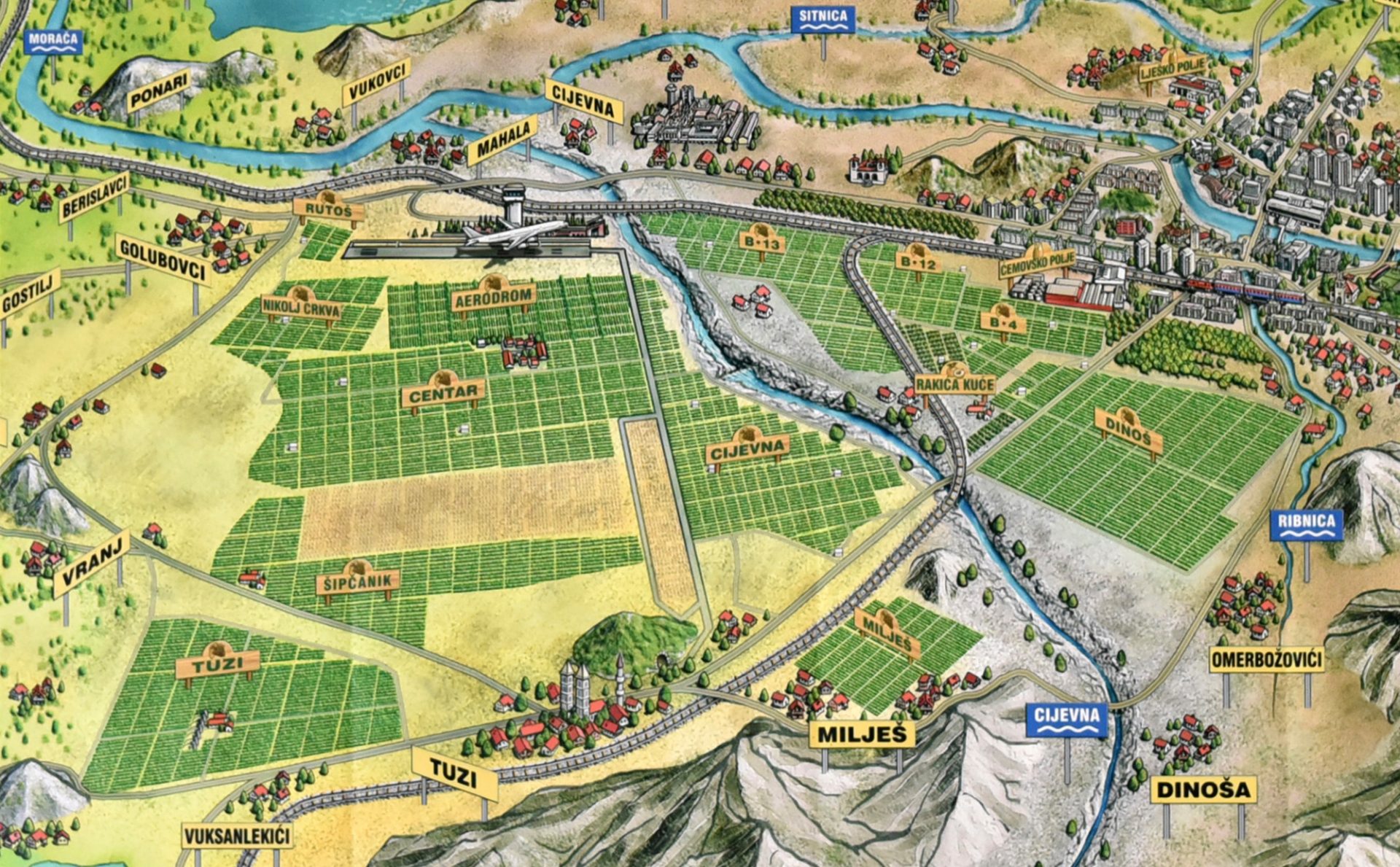

Ćemovsko Polje (Ćemovsko Field), near the capital city of Podgorica, is spread over 2,310 hectares. That’s about 5,700 acres, or one third the size of Manhattan – a rather eye-popping mental image for the wine drinker. Or, if you prefer: 11.5 million grapevines, mostly harvested by hand, neatly aligned in rows whose total length is roughly equal to the distance between the vineyard and Chicago – a rather dreadful mental image for the workers who pick those grapes. And this immense field belongs to one company, producing almost 80% of Montenegrin wine: Plantaže.

Winemaking in Montenegro can be traced back to the days of the Illyrians, when vines were planted on the shores of Lake Skadar. Later on, the Romans brought their own know-how and recorded the indigenous grape varietals. Grape growing continued through Antiquity, the Middle Ages, and beyond, with Lake Skadar and the Crmnica region (between Lake Skadar and the Adriatic Sea) as the main producing areas. Crmnica, in particular, enjoyed a good reputation: to achieve better quality, some wines were stored there in oak barrels, buried deep in the ground, and held for two years; it was also from Crmnica that the Vranac varietal spread to the rest of Montenegro. In the second half of the 19th century, during the reign of Nikola I Petrović-Njegoš, the first regulations in grape and wine production were set. In particular, the sovereign introduced a law mandating that before getting married, each groom from a winemaking region had to prove that he’d planted 100 to 1,000 grapevines.

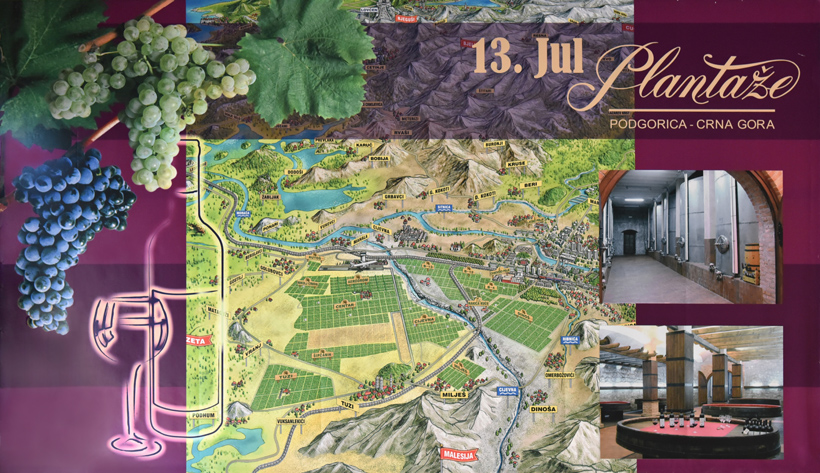

But modern Montenegrin viticulture really started with the founding of Plantaže. Many families had been producing wine for home consumption for generations, yet I’ve been told that on a commercial scale, until the early 1960s, winemaking was just a branch of fruit farming. I can’t say that I understand the implications of that, but it doesn’t exactly conjure images of high-quality wine, which would take a bit more than just fermenting grape juice in a factory. This changed in 1963, when several farms in the areas of Podgorica, Danilovgrad, and Virpazar (in the Crmnica region) were joined to form Agrokombinat 13. Jul (“Agricultural Combine July 13,” in reference to the country’s Statehood Day), later renamed 13. Jul – Plantaže (literally “July 13 – Plantations”). The agrokombinat became a modest winery, with about 200 hectares / 500 acres of vineyards and only three products: a red wine (a Vranac), a white wine (a Krstač), and a rakija (wine brandy).

Like any self-respecting communist state enterprise, Plantaže was dreaming big. Certainly, a vineyard near Titograd – “city of Tito,” Podgorica’s official name from 1946 to 1992 – had to be superlative in some way. In 1970, the Workers’ Council of the company decided that they wanted to expand the vineyard and the production in earnest. The Ćemovsko Field project was born: 2,000 hectares of vineyards and orchards, a plant capable of processing 3,000 tons of grapes, and a wine cellar with a capacity of 190,000 hectoliters. Planning and funding took years, but work finally began in 1977, and 9 million grapevines were planted by 1982. Ćemovsko Field was transformed into one of the Balkans’ best vineyards.

The location wasn’t random. Ćemovsko Polje enjoys unique conditions for wine growing, thanks to its situation between the Adriatic Sea, Lake Skadar, and the Dinaric Alps. Summers are hot and dry, winters are colder, and the vineyard receives over 2,500 hours of sunshine a year, spread over 290 days. The chalky limestone soil benefits from drip irrigation, and large pebbles retain heat that releases into the vines at night.

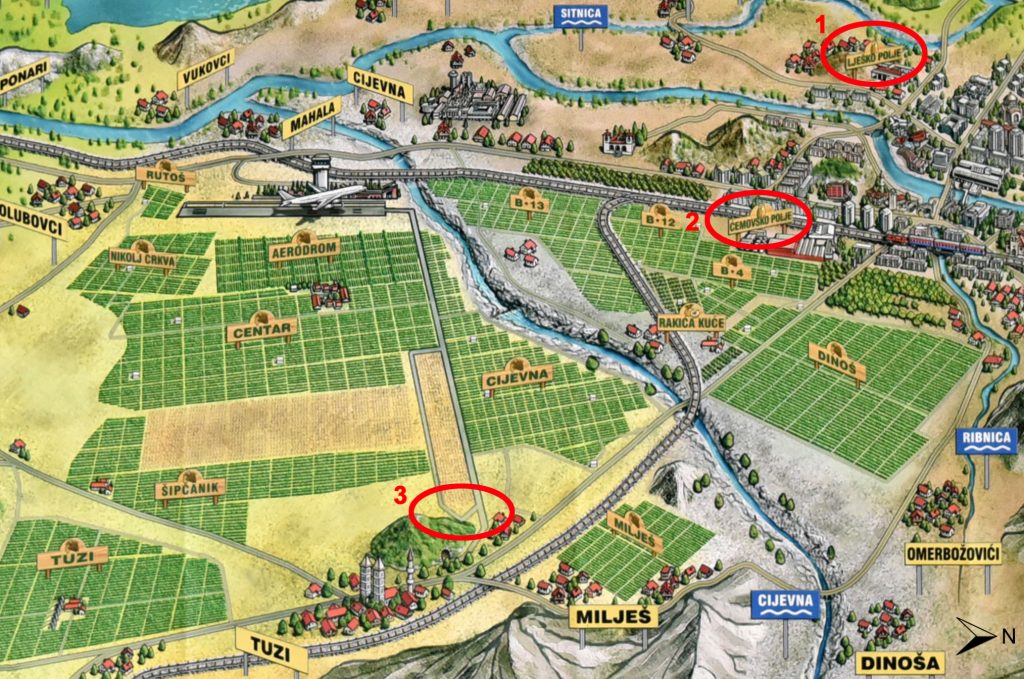

Today, there are about 4,400 hectares of vineyards in Montenegro, of which more than 50% belong to Plantaže. The agrokombinat‘s original vineyards of 1963 are gone, restituted to their former owners, and the country now counts two primary wine regions: the region around Podgorica, dominated by Ćemovsko Polje, and the Crmnica region near the Adriatic, exploited by smaller wineries. There are three cellars handling Plantaže’s large production (22,000 tons of grapes in 2016, turned into 17 million bottles of wine):

- The old cellar in Lješkopolje, with a capacity of 3 million liters.

- The larger new cellar, at the edge of Ćemovsko Polje, with an amazing capacity of 28 million liters; it also serves as company headquarters.

- The Šipcanik wine cellar, an event space with a very special history, where another 2 million liters of wine are kept in barrels.

You can see the three cellars circled on the map below:

Not content with its quasi-monopoly on Montenegrin wine, Plantaže also owns peach orchards, an olive grove, and a huge fishpond from which they supply 100 tons of Californian trout! They also run two restaurants – more on this later. The video below gives a great overview of the company for its 55th anniversary, with a full serving of Yugo-stalgia (unfortunately it’s in Montenegrin only):

My visit to Plantaže begins in the old cellar in Lješkopolje, in southwest Podgorica. Back when the agrokombinat started, this was where all the wine was made, and there was a vineyard next to it. Although the bulk of the production has been transferred to a new facility, the old cellar has been renovated and produces some of the company’s top wines.

In a front room set up as a small museum, we see a few testimonies to the agrokombinat‘s humble beginnings, mixed with various antique wine paraphernalia: a 1st century wine amphora found near the town of Risan; a manual grape crusher and other winemaking tools; a 1970s bottle of Yugo Vranac from Crmnica (“The Black Mustang”) with a drawing of picturesque Sveti Stefan on the label because why not; satirical cartoons mocking Montenegrins’ obsession with Vranac.

Already in the museum room, there are pipes and manways hinting at large tanks right behind the wall. Like pretty much everything else we’ll see in the old cellar, these tanks are still in use.

But let’s start at the beginning of the production.

The “production line,” where the crushing and fermenting happen, is actually located outside of the building. The equipment is brand new, and the temperature of the tanks is controlled thanks to water circulating around them, so that the fermentation takes place in a strictly controlled environment. Apparently, there’s a growing trend for placing fermentation tanks outdoors, and this certainly saves space in the cellar for aging more wine in barrels and in bottles.

At the time of my visit, there are eight people working in the old cellar. The whole company counts about 700 full-time employees, but in the summer an additional 1,000 seasonal workers are hired for the harvest, which usually starts in early August (sometimes even earlier if the weather’s been really dry and hot) and finishes around the end of September (or in early October for late-harvest wines).

Next to the fermentation tanks, we spot the old crusher that was in use here until the 1970s:

Back inside, the cellar is laid out on three levels, and it is indeed filled with barrels and bottles – and tasting rooms. Several rooms contain hundreds of traditional 225-liter barriques. 80% of the barrels at Plantaže are French oak, but there’s also 15% of American oak and 5% of Slavonian oak, the latter being more experimental. All the barriques come from the French cooperage Nadalié, and their heads indicate the product line (e.g., Privilège, as seen in the picture below) and toast level (e.g., noisette, which is between light and medium toast). The barrels also bear identifiers that allow careful tracking throughout the wine’s life cycle. They’re sampled every month to check the condition of the wine, how the wine is developing, and what can be expected in the future. Since it’s recommended that the barrels be used for no more than three to four fillings, so that the oak brings its characteristic tertiary aromas before wearing out, the winery replaces them at a rate of 20-30% per year – a fairly substantial expense at $700-plus a piece. Once the barrels no longer contain wine, they are either sold to distilleries, or turned into furniture and other decorative elements, some of which end up in the tasting rooms.

Some other rooms contain much larger casks, with capacities reaching up to 10,000 liters. These casks are made by Italian cooperage Garbellotto, and can be used for over 20 years. Plantaže has not yet had to go through the delicate task of replacing them, since they were acquired in 2007. Apart from the size, the difference between the barriques and the casks is that the casks will not impart oaky tertiary notes to the wine.

But what are those tertiary aromas I keep talking about, anyway? Well, wine aromas can be divided into three categories. Primary aromas are those specific to the grape variety itself, such as fruit, flower, or herb. Secondary aromas are those derived from fermentation, such as bread, mushroom, cream, or butter. Tertiary aromas are those that develop through either bottle or oak aging, like vanilla, nuttiness, coffee, and tobacco.

We take a small break from winemaking to look out the window. From here, we can see about 2,000 olive trees nearby, and there’s another 8,000 trees in the vineyard (an interplanting practice that I saw in Croatia too). Plantaže started making olive oil in 2017, and uses five different olive varieties – one local, one Croatian, two Italian, and one Spanish. Because of the limited production, their oil, sold under the Plantaže brand, is only available in the company stores at the moment.

We’re going deep underground now – seven meters, to be precise – under the barriques. This is where the tasting rooms are located and where most of the library wines are kept. And once a week, a small TV show is filmed here!

We walk past stacks upon stacks of reserve wine, piled from floor to ceiling: the occasional méthode champenoise sparkler, Cabernet Sauvignon and Vranac from the 1990s, the rather absurdly named and now discontinued Monté Cheval (a Vranac with a French name that means nothing in French). We see some of the Stari Podrum wines (Stari Podrum means “old cellar”), a line of some of the best the winery has to offer. The Stari Podrum Cabernet Sauvignon 2012, for example, won a gold medal at the Decanter World Wine Awards in 2017.

Plantaže offers about 40 different wines made with 28 varietals, 24 of which are international, and the other 4 indigenous. There are 3 méthode champenoise sparkling wines: two whites (one semi-dry and one extra brut) made with Krstač and Chardonnay, and one rosé made with Grenache and Cabernet Sauvignon. The still white wines also use Krstač and Chardonnay a lot, plus Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Blanc, and Malvasia. The reds include Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Petit Verdot, and what can only be called a shitload of Vranac. In addition to the wine, there’s rakija (fruit brandy) of course: three kinds made from grape (Kratošija and Vranac) and one made from peach.

It’s probably time to talk a bit more about the ubiquitous Vranac. Vranac is the Montenegrin red wine grape par excellence. It’s the most important varietal in Montenegro, and one of the most important in Macedonia (oh, sorry Greece, I mean North Macedonia!), and it’s mostly unheard of everywhere else. The grapes grow in small clusters that have a high sugar content, and combined with the vineyards’ climate, they produces aromatic, full-bodied, high-alcohol wines that make you wonder why other countries haven’t tried growing their own. Vranac is also characterized by a very dark color; a deep, dark red with a purple hue – for that very reason, it was once called black wine, rather than red.

Vranac is the main varietal at Plantaže. It covers 70% of the vineyard, has its own geographical indication of origin, and goes into many, many wines. There’s an everyday Vranac and a Vranac for your heart (Vranac Pro Corde). A Vranac that commemorates the 50th anniversary of the winery and the 200th anniversary of the birth of Njegoš. A late-harvest Vranac dessert wine. There’s a Vranac Barrique, a Stari Podrum Vranac, and a Vranac Reserve. Finally, there’s the Sistine chapel of Vranac: the Premijer. Made only from the best vintages, aged in wooden barrels for 4 years then in the bottle for 3 more, it has consistently won prizes at international competitions, in particular the Decanter Wine Awards. And then, all the grape rakijas contain some Vranac too.

Several old Vranac wines have pride of place in the library wine collection. Below, on the right, is one of the oldest bottles in the cellar, a Yugoslav Vranac – Plantaže’s “first quality red wine,” I am told. The wine on the left is no newcomer either; it’s aVranac Lesendro 1979, named after the Lesendro Fortress on Lake Skadar. As that stronghold was built by Njegoš and became the object of several tumultuous battles with the Turks, its very important place in the history of the country was reason enough to name a wine after it. Supposedly, this is the oldest wine in the cellar that remains in good, drinkable condition.

Speaking of tasting, the time has come for us to try some wines! There will be only two wines here in the old cellar, though many more will follow later on in the visit. The wines are served with three cheeses: two from Njeguši, and an Italian blue (Montenegro doesn’t make blue cheese).

The first wine we try is a Chardonnay Barrique 2017, taken straight from the barrique but almost ready to be bottled. This wine is aged in American oak for 8 to 10 months, using bâtonnage – a method consisting of occasionally stirring the lees at the bottom of the barrel, either using a baton or by turning the barrel. The result is a rounded, full-bodied wine with more tertiary notes. Still unfiltered, this Chardonnay has a golden yellow color. The alcohol content, at 14.5%, is high for a white wine. On the nose, it’s quite different from the Chards in the parts of Europe that enjoy a continental climate. Here, thanks to the high number of sunshine hours per year, the primary aromas include tropical notes in the background, such as a hint of pineapple, next to the more continental pear. Toasted bread counts among the tertiary notes, and the wine also has a full-bodied creamy taste, thanks to the bâtonnage and longer lees aging. A very good Chardonnay indeed.

Our second wine if of course a Vranac, but a very special one. This 2013 vintage has been aged for over 4 years in barrels (so far), and is only available at the old cellar. At least, there was no plan to bottle it at the time of our visit; the closest one could get in bottles would be a Vranac Reserve. This is a wine that Plantaže is very proud of and uses as a gauge by which to judge and improve the quality of its other red wines. We see the characteristic dark red color with hints of purple on the edge. It clocks in at more than 15% alcohol, which is again considerable for the region. On the nose, we (well, a little bit I, but mostly the professional winemaker) smell ripe cherries, dried figs, and hints of chocolate in the background, and I might say leather too. On the palate, we taste some fruitiness accompanied by some noticeable but not overpowering tannins that will help the wine age longer. This wine should be paired with foods with bold flavors, such as Montenegrin beef prosciutto (a specialty made in the northern part of the country), grilled tuna, pungent cheese, or sometimes even spicy meat dishes like goulash. But hey, you won’t go wrong if you enjoy it on its own! To me, this is proof that one can make excellent wines with Vranac.

I leave the old cellar very impressed. Since its inception in the 1960s, Plantaže managed to keep increasing both the quantity and the quality of their products while facing the collapse of a country, war, border realignment, and all the many related economic difficulties. But there’s more to come – stay tuned!