With only three and a half million inhabitants and a territory smaller than the New York metropolitan area, one might think that Moldova doesn’t have any ethnic conflicts. The composition of the population seems pretty straightforward: 70% Moldovans, followed essentially by ethnicities from neighboring countries, such as Ukrainians, Romanians, and Russians. Ah yes, Russia… Sure enough, this last bunch, concentrated in the border region of Transnistria, didn’t really welcome Moldova’s independence when the Soviet Union collapsed. If you check on a map, Russia’s not even a neighbor of the new state.

But Transnistria is a story for another day. In this post, I’m looking at a much lesser-known dissension, and the fate of a handful of irreducible freedom-loving, eastward-looking people of mysterious decent, who once declared themselves independent even one month before Transnistria. The Gagauz!

If you have a particular interest in the region, or devour newspapers from cover to cover, you might have read a short article about Gagauzia recently, such as this one, from which I take the following:

An overwhelming majority of voters in a referendum held in the autonomous Moldovan region of Gagauzia have voted for integration with a Russia-led customs union [i.e., the one Ukraine’s been fighting against].

The chairwoman of Gagauzia’s election commission, Valentina Lisnic, said on February 3 that 98.4 percent of voters chose closer relations with the CIS Customs Union.

In a separate question, 97.2 percent were against closer EU integration.

In addition, 98.9 percent of voters supported Gagauzia’s right to declare independence should Moldova lose or surrender its own independence.

It might help to clarify Gagauzia‘s status. The region declared itself independent on 19 August 1991, but this lasted only a few days. On 23 December 1994, the Moldovan government officially recognized Gagauzia as a “national-territorial autonomous unit”. This state of large-scale autonomy, instead of full-blown independence, persists today.

The first time I heard the name Gagauzia, I actually thought it was a joke, à la Molvanîa. But some might say I wasn’t far from the truth. According to Wikipedia, the Gagauz are a Turkic group of very obscure origin, and the etymology of the ethnonym “Gagauz” is as unclear as their history, but it seems that it was a derogatory term used only by their neighbors. So the name wasn’t a joke, after all: it was an insult!

Truth be told, this isn’t much of a touristic destination. Lonely Planet covers it in a half-page insert, most of which is spent outlining history — the only attraction mentioned is the museum in Comrat, and attraction is a misleading word.

When you enter the territory, there are not even nominal border guards. Instead, only a monument on the countryside road (pictured above) welcomes you with the flags of both Gagauzia and Moldova. My advice to you would be to take satisfaction in having made it that far, snap a few silly pictures of yourself next to the monument, and turn around. Go back where you came from, because you’ve seen all there is to see in Gagauzia.

Yes, there’s a Lenin statue, though not a big one. And yes, there’s the mandatory Soviet factory.

The aforementioned Comrat Museum presents little interest for anyone older than a fifth-grader. Being the only museum in town, it tries to cover a variety of topics, but seemingly without a budget to acquire any objects of value. This results in bric-a-brac including dusty stuffed wild boars, snakes in jars, random medals and certificates awarded to random locals, Soviet posters, B-grade busts, Winnie the Pooh clocks, old radios and other 20th century electronic devices (though I’m not sure these last were supposed to be part of the “collection”).

Perhaps in an unintentionally hilarious attempt to collect funds, the museum sells a few rugs. I had read with prudent curiosity that Gagauzia has a small carpet industry. I’m not sure whether “small” was meant to refer to the industry or to the carpets. Here’s the best that its production has to offer:

In any case, Comrat — 25,000 inhabitants, capital of Gagauzia — is rather ugly, even by Soviet standards. The collapse of communism brought a slew of houses and small business properties, hastily built with cheap materials and without any planning or taste. In the town center, a banner displayed on an abandoned construction site reads “We love you, Comrat”, as if the locals felt that a written confirmation was needed in order to render the sentiment less disputable in a rather bleak place.

The previous day’s rain had given the deserted streets of Chișinău a very atmospheric feel. In Comrat those same showers, though certainly not diluvian, had been enough to plunge the town into darkness. In the neighborhood around our hotel (aka the town center), it took nearly 48 hours for the power to come back, which was basically the duration of our stay. There isn’t much to do in Comrat when there’s light, but it only get worse in the dark.

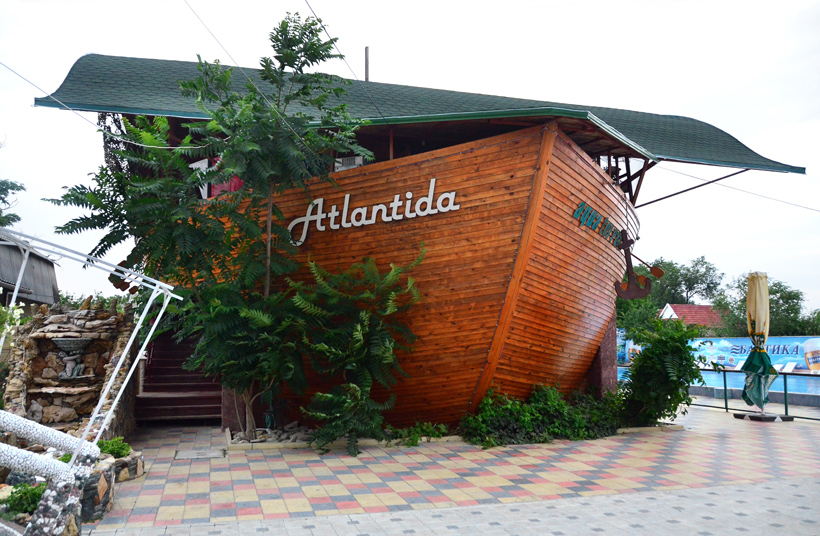

On the food front, my favorite Moldovan cookbook, Sergey Donika’s Moldovan Cuisine, mentions several Gagauz recipes. There’s turshu, a traditional dish of pickled peppers stuffed with vegetables. Or kuzu borzhu, a soup of vegetables and lamb offals. Kavurma, a stew of lamb or chicken, with vegetables like tomaotoes, onions, and peppers. Not to be confused with kivirma, an intriguing cheese pie topped with beaten eggs. Filled with hope, I promptly asked the locals where I could find the finest restaurant in town so I could relish all these rustic-yet-proud almost-national delicacies. The answer was unanimous: restaurant Atlantida was THE place in town.

Atlantida is much more than a restaurant on a fake boat 200 kilometers from the nearest sea. It also comes with a swimming pool and a charming little garden decorated with a bridge and an octopus-shaped fountain made of sea shells. Does YOUR town have anything comparable? I think not. This unique setting provides a quantum of solace where the hard-working Gagauzs can, for the price of a pint of beer, imagine themselves aboard a yacht on the Riviera.

The food, however, didn’t seem to be the owners’ main preoccupation. Except for a large selection of potato chips and other salted snacks proudly exposed on shelves, the menu counted about half a dozen dishes, of the usual Moldovan variety (think gratar) rather than anything specifically Gagauz. We therefore decided to do the only sensible thing: look for another restaurant order two bottles of vodka and a few plates of gratar.

The rest of the evening is a bit fuzzy, but I remember taking the Comrat-by-night walking tour and meeting a couple of young locals who admired our courage because, apparently, walking on the streets of Comrat with facial piercings puts you in great danger of being beaten up, especially after dark. It could be worse, we thought: we could be in Abkhazia.