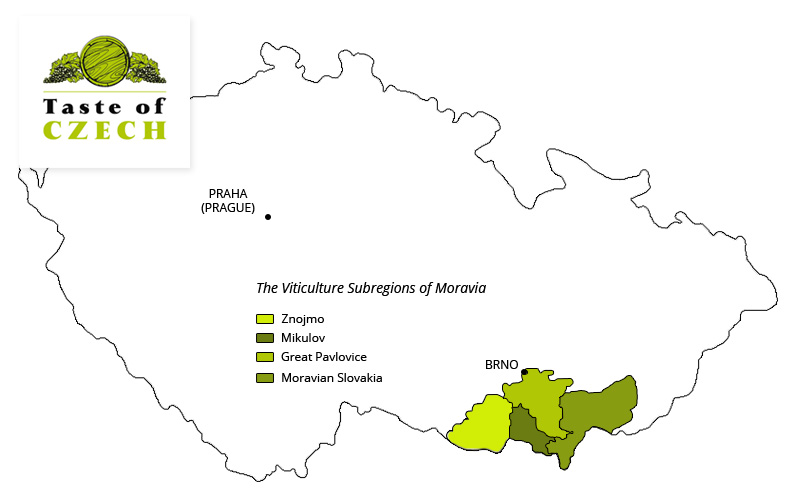

Wait, Czech Republic makes wine, not just beer and neon-green booze? Yes! So let’s start with a quick primer on Czech wine. There are two wine regions in Czech Republic: Bohemia and Moravia (coarsely speaking, the western and eastern halves of the country, respectively). The vast majority of the vineyards are located in southern Moravia, divided into four sub-regions: Mikulov, Znojmo, Velké Pavlovice, and Slovácko (Moravian Slovakia). The first three are named after towns, and the last owes its name to its proximity to Slovakia (duh). In addition to region and subregion, a wine label may also mention a village (obec) and vineyard (trať).

Winemaking in the area dates back to the Romans in the 3rd century, and started in the region of Mikulov, which remains one of the largest wine centers in Moravia to this day. Monasteries subsequently played an important role in growing the vineyards in Medieval times, and in importing French and German grape varietals.

We’re not going to visit any actual vineyards today (for that, I encourage you to check out Czech Wine Adventures), but let’s head straight to the Mikulov region — the heart of Moravian wine country — starting with the town of Mikulov, a picturesque burg topped by an imposing castle. The castle, originally erected at the end of the 13th century, was reconstructed in the first half of the 18th century under the purview of the Dietrichstein princes (a little more about that in minute).

While the castle’s living quarters, with their beautiful furniture, sumptuous library, and sweeping views are all well and good, the part that’s of most interest to us here is the cellar, home to a gallery of wine-making presses and a truly gigantic barrel. In the 16th century, vineyard planting reached a peak. After the Mikulov estate was purchased by Adam von Dietrichstein, ambassador to the Spanish court, vineyards were greatly expanded and new cellars were built at the castle. In 1643, Adam’s grandson, Prince Maximilian von Dietrichstein, commissioned a giant Renaissance wine barrel in which to store the wine collected as tax payment from the peasants who rented his vineyard land. With a length of 6.2 meters, a diameter of 5.2 meters, and a capacity of about 101,400 liters (that’s 135,200 bottles!), it had to be built directly within the cellar. This is one of the largest extant barrels in Europe, and the biggest in Czech Republic, with the added appeal that it actually contained wine at some point.

Nowadays, however, there’s no wine to be had in Mikulov castle —for that, we must head to Valtice. A 15-minute drive from Mikulov, this is another castle town with another wine cellar and many nearby vineyards (although, in this case, palace would be a more appropriate term than castle).

If the Baroque palace and gardens are reason enough to visit Valtice, the additional draw, even more so than in Mikulov, is the wine cellar, because it now hosts the Salon of Czech Republic Wines. Make sure to reserve enough time for this vaulted cellar, as it gives you the opportunity to taste the country’s hundred best wines (plus a few more), with a selection changing every year. Pay a flat fee (about $15), grab a glass, and just help yourself to any wine you like!

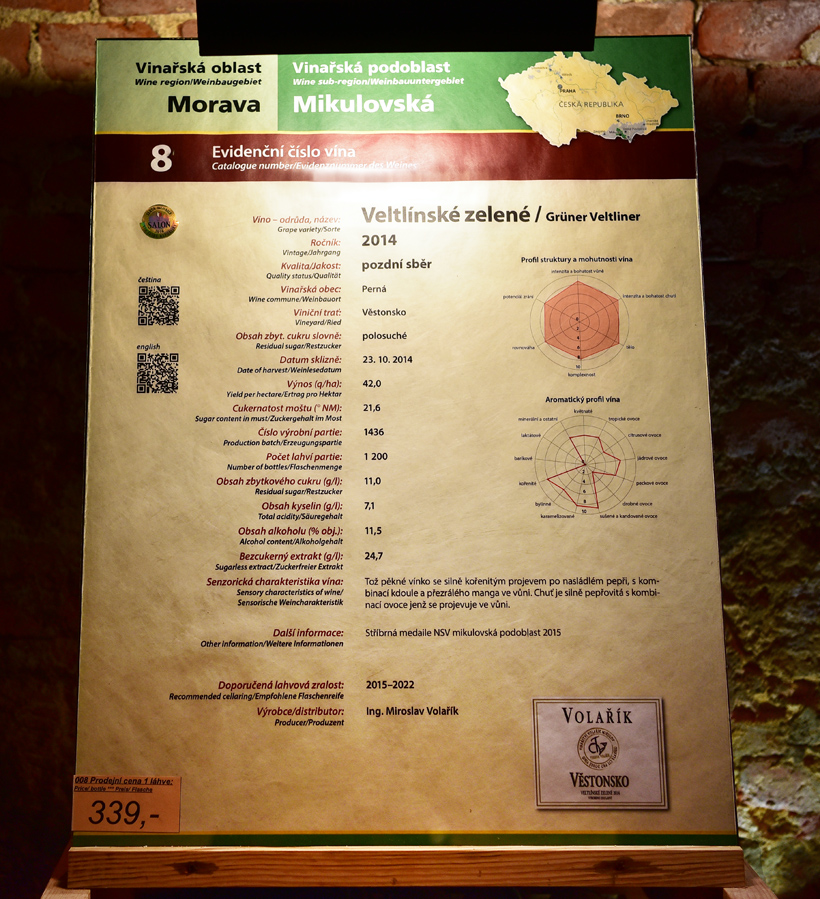

The wines are presented in the order in which you should taste them: first dry and semi-dry whites, then semi-sweet whites, then reds, and finally sparkling and dessert wines. Within each category, they’re further grouped by varietal. Just bear in mind you probably won’t be able to taste all 100 of them, so it’s wiser to skip a few here and there than to naively try the first 20 and then stop. For each bottle, you get a detailed description, production data, and aromatic profile; if you can read Czech, you can educate yourself while getting drunk.

It behooves you to understand the Czech wine classification. At a high level, from lowest to best quality, you’ll find: stolní víno (“table wine”, wherein the grapes can come from anywhere in the E.U.), zemské víno (“country wine”, produced from grapes originating in Bohemia or Moravia), jakostní víno (“quality wine”, wherein the grapes originate from a single wine region in Czech Republic), and jakostní víno s přívlastkem (“quality wine with special attributes”).

That last type has several subcategories, depending on what these “special attributes” actually are. A first series of terms applies to the must weight — that is, the amount of sugar in the grape juice. In order of increasing sugar amount: kabinetní víno (“kabinett wine”), pozdní sběr (“late harvest”), výběr z hroznů (“special selection of grapes”), výběr z bobulí (“special selection of berries”), and výběr z cibéb (“special selection of botrytis-affected berries”). Yet keep in mind that the amount of sugar in the grape juice doesn’t tell you much about the residual sugar in the final wine (it depends on the vinification process); and don’t be fooled by the term “late harvest”. A pozdní sběr wine has very little to do with what’s called late harvest in France or the USA — it does not mean dessert wine. Many pozdní sběr wines, white or red, are dry. On the other hand, výběr z bobulí and výběr z cibéb do tend to be semi-sweet or sweet, as there’s only so much sugar you can turn into alcohol before your yeast dies.

Then there are dessert wines made following a “special” process (still considered “quality wine with special attributes”): ledové víno, (“ice wine”, wherein grapes are still frozen when being pressed), and slámové víno (“straw wine”, wherein the grapes have dried for at least three months on straw mats or hung in a well-ventilated space).

You can look at the full Salon catalog from 2016 (the time of my visit), but here are some tasting notes and a selection of the wines I liked best (incidentally, I don’t have a single favorite in common with the selection from Czech Wine Adventures). I don’t claim to have tasted all 100+ wines on offer, but I tried my best!

The whites are all very light, and some of them can have an overly floral nose. I tend to like the semi-sweets a little more. In particular, I think the wines made with Pálava (a cross between Müller Thurgau and Gewürztraminer that’s grown almost exclusively in Moravia) are much better when they’re sweet, as they’re much too floral for me when dry. Some of the Rieslings are so light they have a sugared water quality. I also found a few wines that were very oaky but sweet at the same time, which was new to me.

My selection of whites:

8 – Volařík, Gruner Veltliner 2014 (Mikulov subregion), pozdní sběr, semi-dry.

16 – Château Valtice, Premium Collection Pinot Blanc 2013 (Mikulov subregion), pozdní sběr, semi-dry, with a nose of lychee and cantaloupe.

24 – Kosík, Chardonnay 2012 Tadeas (Slovácko subregion), pozdní sběr, semi-dry and matured in oak barrels for 24 months.

58 – Winberg Mikulov, Pinot Blanc 2014 (Mikulov subregion), výběr z hroznů, semi-sweet, made from 50 year old vines.

There are only half as many reds as there are whites (and only one rosé). I particularly like the ones that show notes of cooked berries: strawberry preserves, blueberry jam, blackberry jam, and blackcurrant pie come back often in the sommelier-written aromatic profiles. They may not be incredibly original, but they’re pleasant to drink.

My selection of reds:

76 – Vinselekt Michlovský, Cabernet Sauvignon 2013 (Mikulov subregion), výběr z hroznů, dry.

80 – Vinselekt Michlovský, Laurot 2012 (Mikulov subregion), výběr z hroznů, dry; Laurot is a hybrid showing characteristics of both Saint-Laurent and Merlot (hence the name).

I don’t remember trying any sparkling wines. The dessert wines are good but classic, with smells of apple compote and honey (except for #96 below). They’re generally very sweet, with over 150 g / l of residual sugar, and don’t have much of an acidic finish.

My selection of dessert wines:

96 –Oldřich Drápal, Cuvée Bobulky od Kapličky 2013 (Velké Pavlovice subregion), slámové víno, sweet: interesting, floral (honeysuckle?) and peppery nose, quite peppery on the palate, with hints of orange.

98 – Château Valtice, Pinot Blanc Výběr z Cibéb 2013 (Mikulov subregion), výběr z cibéb, sweet: nose of apple and apple compote.

Should you seek out Moravian wine back home? Probably not, because imports are limited and you have plenty of equally good or better options. Will you enjoy drinking it its natural habitat? Absolutely. Most of these wines are forgettable but nonetheless enjoyable, and they certainly don’t break the bank. Some of them are very good, and you’re still unlikely to pay more than $15-20 a bottle. Anyway, do you think all the wines made in Bordeaux are worth drinking?

Ideally, I’d use this freshly acquired knowledge to go back and visit the wineries themselves. The Mikulov subregion in particular produces most of the wines I liked in this tasting. I’m sure one could spend a wonderful summer vacation biking drunkenly from one vineyard to the next between lunch and dinner — not to mention that several wineries seem to do double duty as B&Bs. Maybe next time…